Renewing innovation

Innovation is one of those words in higher education that people have come to dread. Administrators love it. Faculty members who style themselves as "futurists" -- as opposed to teachers -- love it. But it is used so often that it stops sounding like a real word after a while. Or when it has meaning, it is merely code for "unfunded mandates" or "unpaid labor".

This is all too bad, because I think innovation in higher education is a noble idea. In fact if we look at it right, it could be a north star for pulling ourselves out of the current post-Covid malaise we find ourselves in.

Three axes of innovation

Google's definition of "innovation", used for its own business, has three components: It's something that's new, surprising, and radically useful. A thing is innovative to the extent that it exemplifies all three of these.

For example, take just a couple of items from Popular Science's top 100 innovations of 2022:

- Phone (1) from Nothing. What's new and surprising about it: It's an Android smartphone that has a screen, but you're not supposed to look at the screen most of the time. Instead, it has a system of lights on its back that can be programmed to light up in different configurations depending on what is happening on the phone -- with the intent that you look at the lights, not so much at the screen. What's radically useful: It (supposedly) cuts down significantly on the amount of time spent looking at the screen and being distracted by apps.

- Voterra electric firetrucks. What's new/surprising: EVs aren't new, but ones at this scale are. What's radically useful: Other than the lack of reliance on fossil fuels, these electric trucks can be moved around within a fire station without spewing exhaust into the enclosed space.

Getting just two out of three or one out of three axes right, means that the thing is not really an innovation. For example, a phone that just has pretty lights on the back that turn on randomly, or can't be configured into notification patterns, might be new and somewhat surprising -- but it's not very useful. A new model of electric pickup truck (as opposed to a fire truck) would be useful and somewhat new (as there aren't very many EV trucks on the market yet) but not surprising.

In higher education, unfortunately, these three aspects of innovation spell trouble:

- Things that are new in higher education are easy. Too easy. Once you get the right people on board with it, the friction of launching a new initiative at a university is near zero. It takes very little effort to launch an initiative. Just look at any college or university and you'll see a superabundance of new stuff being launched. (Except new tenure-track positions.) Everybody loves launching initiatives, and then using them for PR purposes. However:

- Things that are surprising in higher education, on the other hand, are often viewed as dangerous. Ask any professor who's tried, for example, to use alternative grading or flipped instruction where those ideas were uncommon. This is because universities, for all the accusations of being liberal breeding grounds, are among the most organizationally conservative institutions in human history. "Surprising" means change, and change is one of the most difficult and fraught subjects in higher education. And finally:

- Things that are radically useful in higher education are hard work. It's relatively easy to design and launch a new initiative. It's much harder to connect initiatives with the people they affect, track how well the initiative is doing in serving those people, and make informed changes over time using clear criteria for what "success" looks like. In other words, it takes sustained attention and significant investment to make a new initiative actually work, and in my experience, both of those -- attention and investment -- are weak links in most higher education institutions.

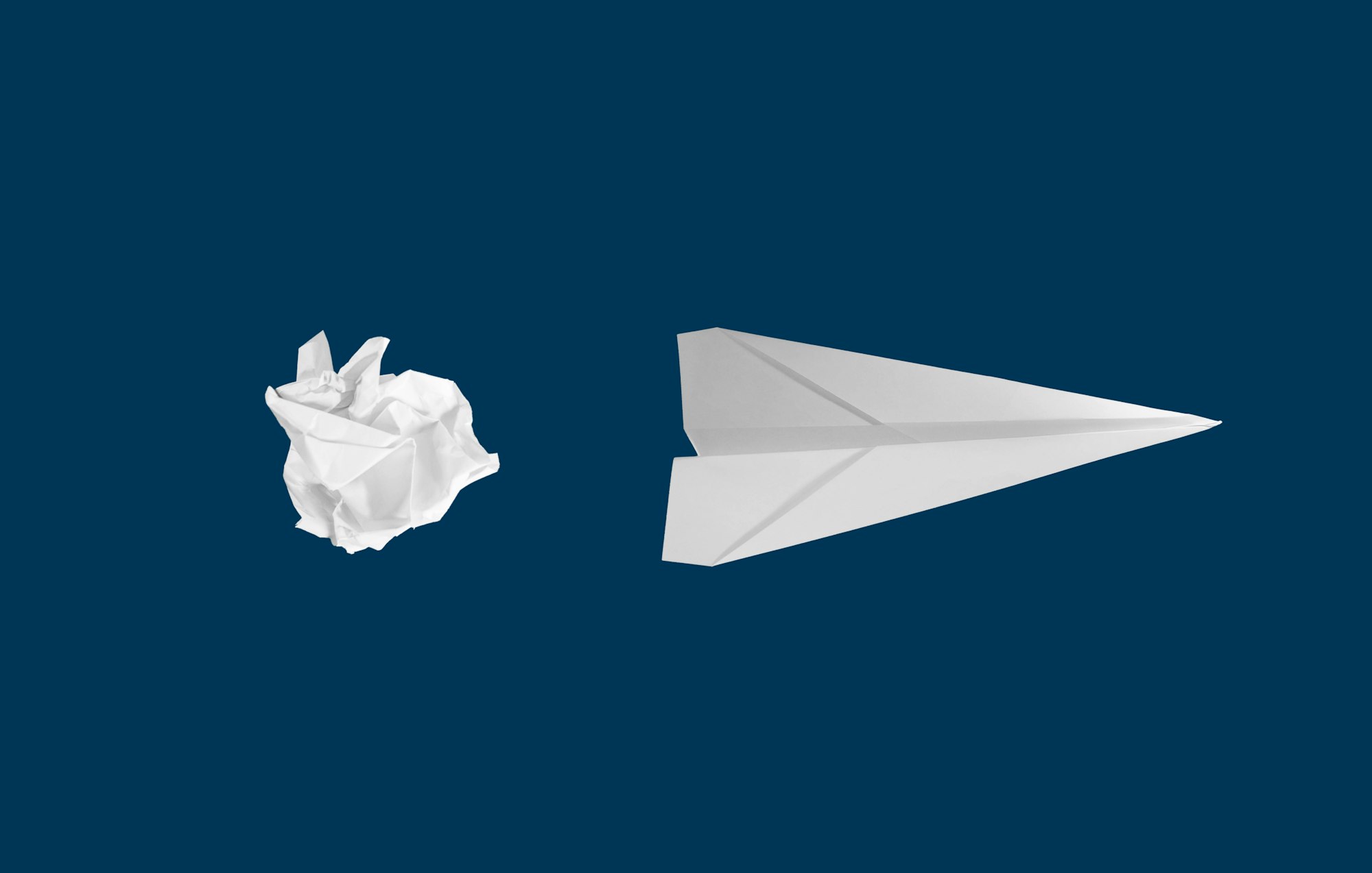

Real innovation is hard work and entails significant risk. Many universities and colleges run away from, rather than toward, both hard work and risk. This is why, when you look around at "innovation initiatives" at many universities and colleges, you find the academic equivalent of phones that light up randomly or just another electric pickup truck. They're pretty, and attention-grabbing, but not useful; or useful but not really different from the status quo. Look closer and you'll see that many of these initiatives are simply the top layer of a landfill of previous initiatives that launched with high hopes and great fanfare, but end up as derelicts or shipwrecks in short order.

What innovation really means

I've written about innovation before, and I've been steeped in it throughout most of my career. I saw what real innovation looks like up-close during my sabbatical at Steelcase. And I've come to strongly dislike "cheap" innovation, that is, attempts at innovation that only address one or two of the three pillars I mentioned above.

But as much as I thought I understood innovation, I was surprised recently to learn that if you look at the etymology of this word, you end up with the word innovacion, which means renewal.

Think about the implications of this root word for a minute, and think about any "innovation initiative" you've experienced recently. Does it renew your institution in some way? Does it renew you? If it doesn't, then it's not really innovative. It's just one more damned thing to do, probably by somebody without the bandwidth or pay scale to see it through.

Faculty and staff these days need renewal: Something that refreshes our experiences and our commitments to working in higher education, something that reminds us why we work in this weird industry sector in the first place. Institutions need renewal too: Because the ground on which they're founded has shifted utterly since 2020, and the former ways of conducting themselves are showing signs of buckling and collapse.

Innovation that doesn't renew, is just someone's pet project that's been imposed on other people and bolted on to an existing structure. It's not what I would call real innovation. Real innovation involves at least three things:

First, real innovation sweats the details. It's not just a cool-sounding idea that's been given a name. It's been operationalized. It comes with plans and blueprints and a commitment to stick to the plan. (Which includes a plan for how to stick to the plan.) It entails careful research before, during, and after its implementation with objective evaluations and plentiful feedback. If it's just a breathless idea or a vision of a possible future, it might be compelling, but it's not innovative. (Primarily because it's not useful if there's no research, no contingency plans, no definition of success, and so on.) Every big idea sounds great when it's in the abstract. It's only when you start spelling out the fine details that you discover if it's really a good idea.

Second, real innovation requires making decisions. Recently I wrote at Intentional Academia about the meaning of "decisions": The word, decide, is related to words like homicide and suicide. Making a decision to do a thing is also thousands of decisions not to do all the other things, and in that sense, it's putting those other things to death. Academics are terrible at making decisions; we want to do all the things all the time. But when you decide to implement an initiative, you can't just bolt it on to an existing superstructure. Seeing the initiative through takes time, resources, and energy. Therefore, unless you want to be the one who asks faculty to do One More Damned Thing, other things have to be shut down in order for faculty, staff, and students to find the bandwidth. And, if the initiative you're starting is really working (which you would know if you had sweat the details) you will need to make a decision about scaling it up; likewise if it's not working, you have to make a decision about shutting it down. So our ability to be really innovative in higher education is only as good as our ability to have the courage to make real decisions.

Third, real innovation is everyone's job. I'm suspicious of positions that have the title of something like "Chief Innovation Officer" or "Vice Provost for Innovation" because there's an implication that innovation is "owned" by one person or one office. Innovation is that person's problem. But truly innovative ideas throughout history have been inextricably linked to entire communities of people, not just a person who is "in charge of innovation". Innovation that doesn't scale is ineffective. It cannot be somebody else's problem. It has to be something accepted as a community-wide commitment, or else it's just someone's pet project.

I wrote a proposal recently for a project at my university that involves teaching and learning innovations. I think the word "innovation" appeared more than a dozen times in five pages. When I gave it to a colleague for feedback, he told me to avoid using that word "innovation" because people today get tired just looking at it.

Innovation that doesn't really innovate – that doesn't renew – is exhausting. But real innovation has the power to motivate and inspire. In fact the primary evidence for its realness is the level of motivation and inspiration you see among rank-and-file higher ed people when you mention it. That's the kind of innovation I hope we strive for these days.