Part IV: Thinking About Thinking

This is part four of a five-part series focused on using thinking routines to drive metacognitive skill building. Click here to revisit my last blog in this series on using the “I used to think…Now, I think…” routine.

To recap, metacognition is a cognitive ability that allows learners to consider their thought patterns, approaches to learning, and understanding of a topic or idea. Teachers can leverage the power of thinking routines developed by Project Zero at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education to help students develop their metacognitive muscles. The thinking routines are a collection of purposeful and structured thinking patterns designed to stimulate students’ cognitive engagement and cultivate cognitive awareness.

Teachers can use these thinking routines to design online or offline stations in a station rotation or embed them into a playlist to encourage students to pause and intentionally spend time thinking about their learning. Thinking routines offer more than just a structured pathway for students to delve into their thinking and explore the content deeply; they also serve as a window into their cognitive processes, offering invaluable formative assessment data.

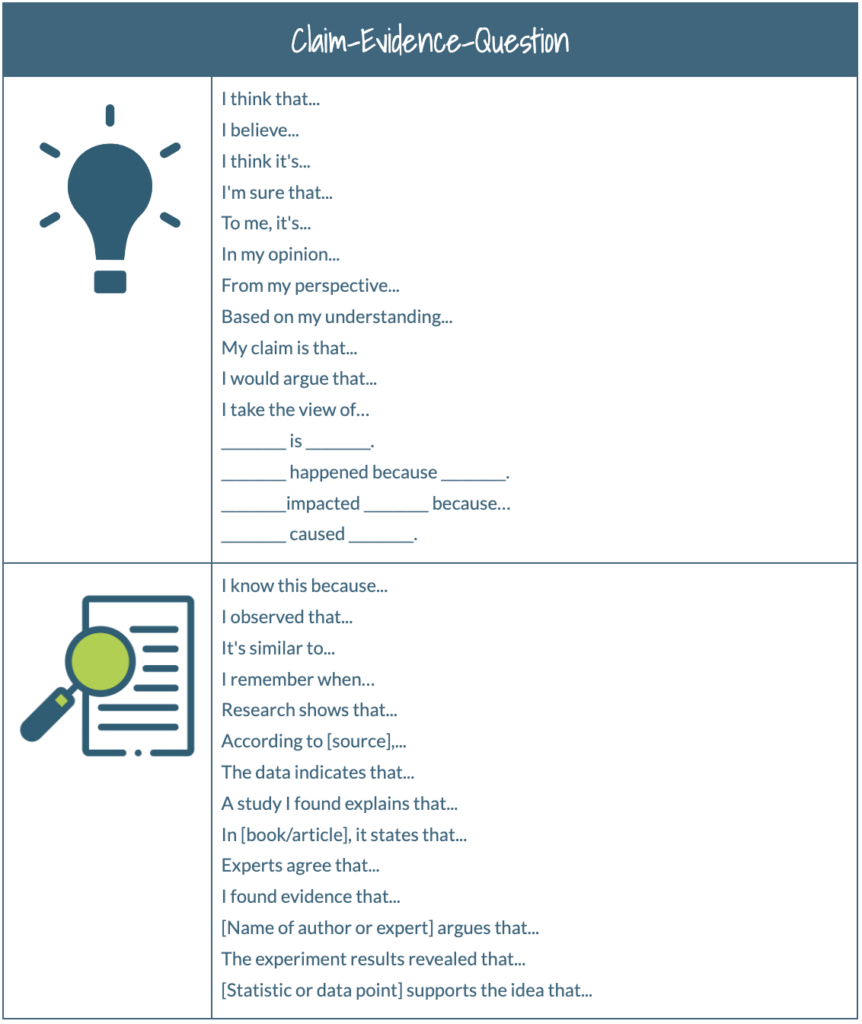

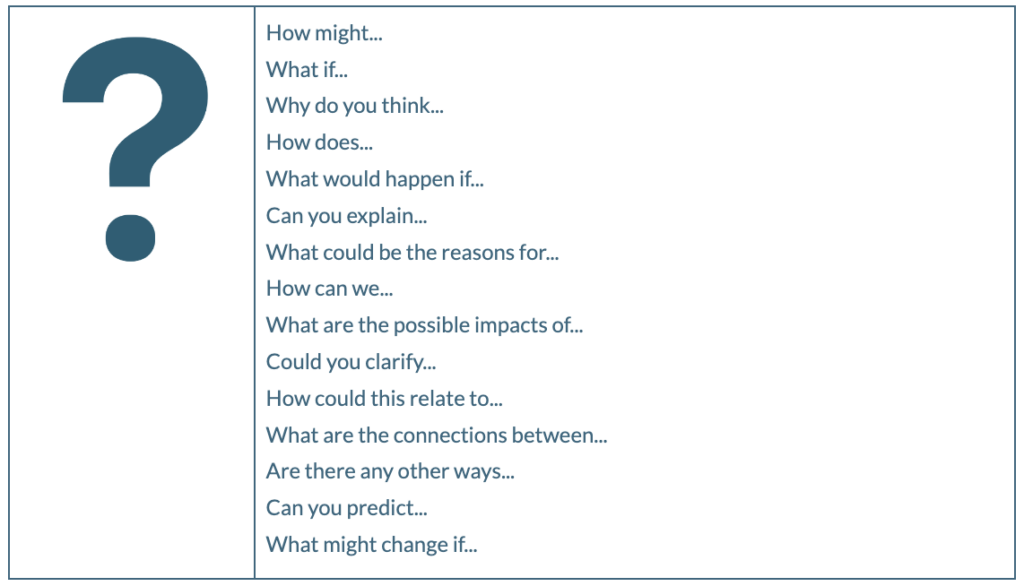

Claim-Evidence-Question Thinking Routine

The Claim-Evidence-Question thinking routine is an instructional strategy designed to promote critical thinking, evidence-based reasoning, and active engagement among students. It encourages students to develop and articulate their ideas, support them with relevant evidence, and generate thoughtful questions that further deepen their understanding and stimulate curiosity. The routine can be applied across various subject areas and is valuable for individual and collaborative activities.

In the Claim step, students are prompted to articulate a clear and concise assertion or statement about the topic. This encourages them to synthesize their knowledge, form their own interpretations, and express their perspective on the matter.

During the Evidence step, students are tasked with supporting their claim with relevant and compelling evidence. This evidence can be drawn from various sources, such as research articles, data sets, personal observations, or historical examples. Teachers can use this step to encourage students to assess the credibility of their evidence and select information that effectively strengthens their claims. This phase underscores the significance of critical evaluation, research skills, and reasoning.

In the final step, the Question phase, students are encouraged to pose thoughtful and probing questions related to the topic and their claim. These questions might explore nuances, seek further information, or address potential counterarguments. By generating these questions, students demonstrate curiosity and an eagerness to explore the topic in more depth. This step also fosters metacognition, as students reflect on what they don’t know and what aspects of the topic warrant additional investigation.

Using Claim-Evidence-Question at the Elementary Level

Literature Analysis: After reading a story or book, students make a claim about a central theme or main character’s motivations, provide evidence from the text, and pose questions about the main idea or character.

Science Experiments: Students make a claim about the outcome of a science experiment, present data as evidence, and ask questions about variables that might have affected the results.

Historical Events: Students make claims about the causes or impact of historical events, provide evidence from historical documents or images, and ask questions about the events that are still unclear or confusing.

Nature Observations: After a nature walk, students make a claim about nature, offer evidence from their observations, and pose questions about animals, plants, or natural phenomena.

Math Problem Solving: Students make claims about solutions to math problems, provide evidence by showing their work, and ask questions about different problem-solving strategies.

Artwork: After viewing a piece of artwork, students make a claim about its meaning, provide evidence by pointing out specific elements in the artwork, and ask questions about the meaning of the piece.

Current Events: Students make claims about news stories, provide evidence from reputable sources, and ask questions about potential consequences or future developments.

Health and Nutrition: Students make a claim about the importance of a balanced diet, provide evidence from readings and other resources, and ask questions about the effects of specific food choices.

Character Traits: After reading about a character in a book, students make a claim about that character, provide evidence from the text, and ask questions about the character’s motivation, relationships, or impact on the story.

Personal Reflections: Students could make claims about their learning experiences, provide evidence from their assignments, and ask questions about how they can improve their skills.

Using Claim-Evidence-Question at the Secondary Level

Literary Analysis: After reading a novel or play, students make a claim about a thematic interpretation, provide evidence from specific passages, and ask questions about the author’s intent.

Scientific Investigations: Students could make claims about scientific hypotheses, provide evidence from experiments, and ask questions about variables, controls, or potential sources of error.

Historical Debates: Students could make claims about historical interpretations, provide evidence from primary and secondary sources, and ask questions about different historical perspectives.

Ethical Dilemmas: Students make a claim or take a stance on an ethical issue, provide evidence gathered from research or their own life experience, and ask questions about the implications of different choices.

Real-world Math Challenges: Students make claims about how to solve a real-world math problem, provide evidence and support with mathematical reasoning, and ask questions about alternative approaches or unclear aspects of the problem.

Artistic Interpretation: Students make claims about the meaning of a piece of artwork, provide evidence drawing from the visual elements and techniques, and ask questions about artistic techniques and/or cultural context.

Biodiversity Loss: Students might claim the reasons for declining biodiversity, provide evidence from ecological studies, and ask questions about the consequences for ecosystems and human societies.

Renewable Energy: Students could claim the benefits of renewable energy sources, provide evidence from energy production data, and ask questions about the barriers to wider adoption.

Historical Comparisons: Students could make claims about similarities and differences between historical periods, provide evidence from various time periods, and ask questions about the factors that influenced change.

Fitness and Health: Students could claim the benefits of a specific fitness regimen, provide evidence from health studies, and ask questions about long-term impacts on cardiovascular health.

In the final post of this series, we’ll delve into the practical uses of the “See, Think, Me, We” thinking routine for educators. Discover how this powerful tool propels students to think deeply, make personal connections, and consider the larger implications of what they are learning.

One response

Claim, evidence, question is such an important process for students to participate in to promote metacognition and organization of thinking. You state, “Thinking routines offer more than just a structured pathway for students to delve into their thinking and explore the content deeply; they also serve as a window into their cognitive processes, offering invaluable formative assessment data” (Tucker, 2023). When we encourage students to explore, create, and think more deeply about content, they form more meaningful connections and solidify lasting learning.

My district uses claim, evidence, reasoning (CER) as the format for creating an answer to a question, gathering evidence from students’ data, and incorporating reasoning to explain a “…rule or scientific principle that describes why the evidence supports the claim” (Brunsell, 2012). The main difference between the CEQ and CER models is the final step in which , “…students are encouraged to pose thoughtful and probing questions related to the topic and their claim” (Tucker, 2023).

Thank you for your post.

Resources

Brunsell, Eric. (2012). Designing science inquiry: claim + evidence + reasoning = explanation. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/science-inquiry-claim-evidence-reasoning-eric-brunsell#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Claim%2C%20Evidence,the%20evidence%20supports %20the%20claim

Tucker, Catlin. (2023). The power of claim-evidence-question. https://catlintucker.com/2023/09/claim-evidence-question/