How We Use Book Clubs to Empower Our Readers

By Sara Kugler

I’m a literacy coach in an elementary school that includes grade six. Each year I co-teach in one classroom during the literacy block, and this year it’s with our 6th graders. I’m fascinated by this age, as I also have my own 6th grader at home. My co-teacher has only ever taught 6th grade and has an affinity for teaching these early adolescents.

Since the start of school, we’ve been noticing a general malaise, a disengagement, and a passivity in many (not all) of our students during whole-group reading instruction. We have some theories…let’s call them “maybes.”

Maybe students developed habits of disengagement and passivity during their year of virtual school. Maybe the class size is so large this year that students are learning they can “hide” and get lost in the shuffle. Maybe our curriculum or teaching style or learning targets or texts aren’t relevant to them and so they feel disconnected and unmotivated. The list of possibilities goes on.

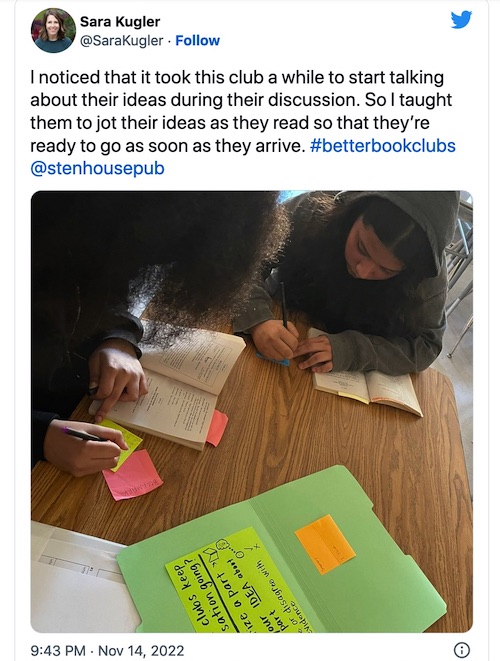

And yet, our time with students in small groups, what we call book clubs, tells a completely different story. They arrive at a small table carrying their chairs, their book, a pen, a stack of sticky notes, and their book club folder. They talk so much I find it difficult to even get a word in and have to use the “Time Out” signal with my hands so that they take a breath.

Students stop me in the hallway and ask, “Is our club meeting today??? I gotta read, then!” They encourage the other members of the club to read more each week so they can find out what happens.

It got me wondering why these students appeared disengaged at one time of the day, and just 15 minutes later, were acting so differently. What are the conditions of our book club-styled small groups that are working for students?

The special qualities of a book club model

One quality of a book club is that it requires its members to be active rather than passive. When I meet with a student book club, my role is to listen, collect some data on the club’s strengths, and teach them a next step. But it’s the students’ job to initiate, sustain, and facilitate the conversation about the book.

During whole-class instruction, on the other hand, students are often asked to listen as a teacher delivers some instruction. In best case scenarios, students are provided time to talk, share, and engage in the lesson, but mostly these are on the teacher’s terms.

Another quality of book clubs is that they are student-centered rather than teacher-centered. During a book club, students sit in a circle, facing each other. Book clubs are brimming with student choice and voice. Students have input about which text they’ll read, how much to read between meetings, and what they might think about as they read.

The teacher could make these decisions for students, but there’s no need – the students have strong opinions about all of it! This is in contrast to whole-class instruction in which students often face a board and a teacher, who delivers a lesson.

Now, none of this is to say that we should eliminate whole-class instruction. It’s helpful to establish a knowledge of shared texts, common ideas and language, and focus our work around collective goals. However, I’m currently reflecting on how much time is actually necessary for this method of teaching.

To reduce the amount of passive, teacher-centered time, one of our goals in our classroom is to keep whole-group instruction to an absolute minimum – 15 minutes or less – so that students can get to the essential work of actively reading, writing, thinking, and talking about their ideas.

Begin a new book club by playing a little chicken

I am struck year after year by the power of listening as a starting point for book clubs. Each time I meet with a new book club, whether I’m new to teaching them or whether they’re a newly formed group, I prioritize listening for a few purposes. One, it establishes my role and their role from the very beginning. I want them to understand that their role must be active because I won’t be doing the majority of the heavy-lifting in the conversation. They will.

As you can imagine, this leads to incredibly awkward initial interactions. I have to admit, I love it. Kids are so used to their teachers (and other adults in their lives) filling the silence and taking over. I like to just stare at a blank piece of paper, pen at the ready, and let some awkward silence fill the air. We are in a dance, playing a little game of chicken.

Another reason I like to start with listening is that it serves as an assessment of both their understanding of the text and their ability to engage in academic discourse. These are some things I want to know:

► Comprehension Lens Questions: What are students thinking about as they read this book? What are they understanding? What ideas do they have about it?

► Conversation Lens Questions: What do students think is worth talking about? How do they discuss their ideas? How do they connect to each other’s ideas? How do they develop their ideas through conversation?

Listening and taking notes or a transcript of their talk reveal some answers to these questions.

Analyzing student talk

Let’s analyze a transcript of a Book Club reading The Secrets of Droon and see what it reveals about what they already know how to do and what I might teach them.

Katrina: I wondered on page fifty-two—why does the air smell like smoke?

Shayla: I’m thinking the person who grabbed her might have stopped because he . . .the king is powerful.

Emma: I wonder why Keeah’s dad kept running after them.

Solei: I could really imagine this land and how different it is from their home. I bet it didn’t even make sense to them at first.

Shayla: Another thing I’m wondering is how that stone is so powerful.

By jotting down a transcript, a few important things are revealed to me about what they’re thinking about and what they know about conversation:

- Katrina and Shayla were monitoring their own understanding of the story and noticed when they were confused. They were using questions to help clarify what was happening.

- Shayla and Emma were grappling with character motivations – why characters do the things they do.

- Solei was visualizing this strange new setting and empathizing with the characters.

I also noticed that their comments didn’t connect to each other. They were reporting their own ideas and then checking out of the conversation. So they seemed to have enough discussion-worthy ideas. I just needed to teach them to listen and respond to each other’s questions and ideas, rather than merely waiting for their turn to share a new, unrelated idea.

Noticing, naming, and teaching independence

Before teaching, I have to remember the qualities of book clubs that have made them so valuable and engaging – they require their members to be active, and they are focused on student choice and voice. If I jump in and start facilitating or prompting with “Who can respond to Katrina’s question?” I’d be taking the active role. Instead, I want to teach students to be independent. To foster this independence, my teaching tends to follow a structure:

- Name what the book club is already doing well.

- Name what you could teach them and why it will be useful to them as a book club.

- Provide some examples of language they might use.

In the case of the above book club, my teaching sounded something like this:

Can I stop you for a minute? Wow – I’m noticing that as a club, you are very strong at coming to the table with questions and ideas that are worth discussing. Everyone in the club was ready with something to say!

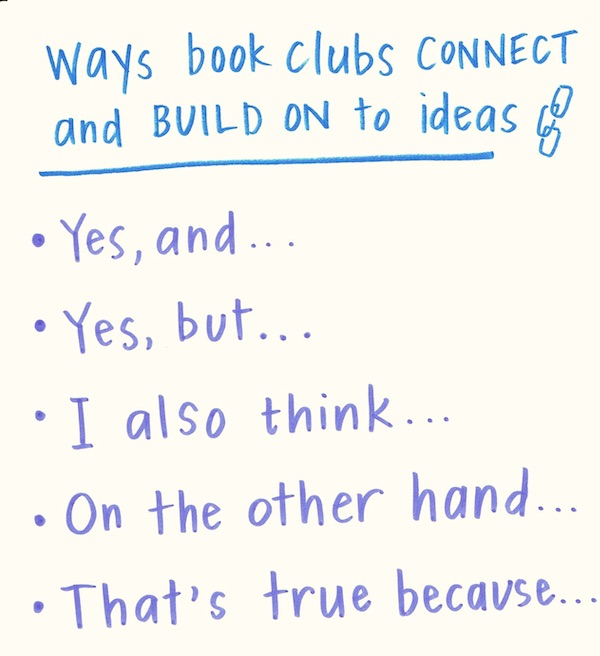

Another thing I noticed was that each person said their own idea, but those ideas weren’t connected in any way. I’m wondering if I could give you a tip about how to build on each other’s thinking, rather than each person saying their own thinking?

To build on, you can listen, and think to yourself, “What do I think about their idea?” Here’s a chart that might help you to connect and build on during your conversation.

Now let’s try it again, but instead of each of you saying your own idea, look for opportunities to connect or build on something someone else said.

Then I grab my pen and look back down at my notes.

Giving students the time and attention to learn

This kind of teaching is challenging because it demands all of our willpower not to jump in, take over, save, or problem-solve immediately. It also requires patience with our students as they stumble and approximate and with ourselves as we analyze our notes and give ourselves time to think about their strengths and needs.

That’s really the big takeaway here. If we want classrooms where students are active, engaged, and centered, we must hold ourselves accountable for listening, noticing, and responding to each of them.

Thanks, @DibenedittoMrs for being my thought partner this year!

Sara is the also the author of Better Book Clubs: Deepening Comprehension and Elevating Conversation (Stenhouse, 2022) where she shares many more ideas about this reading strategy. You can follow her literacy adventures in the classroom on Twitter @SaraKugler.