During my training to become a teacher, I was immersed in the work of Madeline Hunter when it came to lesson plan design. Her Instructional Theory into Practice (ITIP) model helped me identify the strategies I would use on a daily basis to help my students learn. These included the anticipatory set (hook), reviewing prior learning, checking for understanding, forms of practice, and closure. Every lesson had these elements and I often received positive feedback from administrators on these when they observed me. Closure is something I was incredibly proud of and I always ended lessons with some form of paper exit ticket. I shared the following in Disruptive Thinking:

While the opening moments with students are crucial, so are the final minutes. Think about this for a second. What’s the point of an objective or learning target, whether stated, on the board, or students having the opportunity to discover for themselves, if there is no opportunity at the end of the lesson to determine if it was achieved? Learning increases when lessons are concluded in a manner that helps students organize and remember the point of the lesson.

At the time, this model was both a practical and effective means for planning direct instruction and was readily embraced as this was the primary strategy used in classrooms. It streamlined practices in an efficient way that could be replicated day in and day out. Herein lies the main disadvantage of ITIP. It was a one-size-fits-all approach centered on the teacher making all the decisions from an instructional standpoint at the expense of developing competent learners who can think.

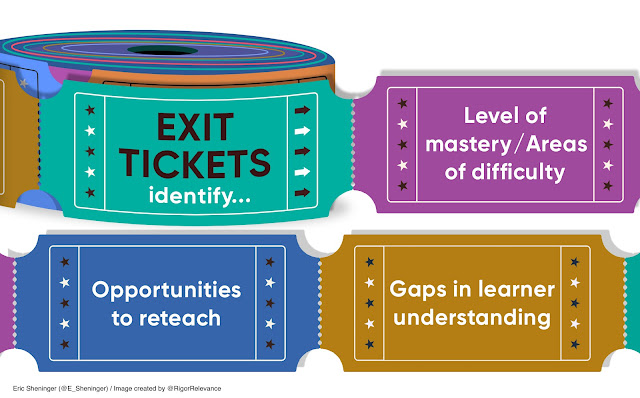

Like many things in education, elements of ITIP still have value depending on how they are used. Closure is still critical, in my opinion, as a means to determine lesson effectiveness and serve as a catalyst for reflective growth. Exit tickets, when constructed well, represent a sound strategy to be implemented at the conclusion of a lesson. In simple terms, these are ungraded formative assessments that assess what students learned during the course of the lesson. The data from then can be used to identify the following:

- Level of mastery

- Areas of difficulty

- Opportunities to reteach

- Gaps in learner understanding

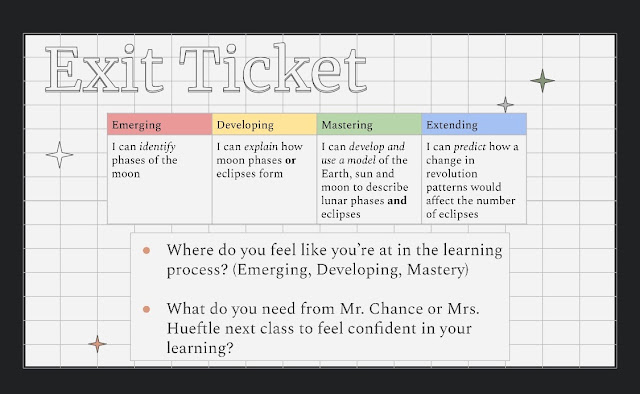

The information gleaned from them provides the teacher with additional insight as to how the lesson went and what can be done to improve it in the future. A recent visit to Quest Academy Junior High School, where I began longitudinal work on personalized competency-based learning (PCBL), got me thinking more deeply about this strategy. The principal, Nicki Slaugh, is a trailblazer in this area and I am fortunate enough to be providing coaching support to her staff to take them to the next level. While visiting classrooms with Nicki, we saw a slew of outstanding practices in action. However, I was incredibly impressed with the exit ticket created by science teacher Melanie Hueftle, which you can see below.

Not only does this meet the criteria for a well-designed exit ticket, but it also goes much more profound and serves as a more powerful reflective tool for both the teacher and the student. As reported by John Hattie, self-reported grades/student expectations are one of the most effective strategies out there (effect size = 1.44). The exit ticket puts the “personal” in personalized as each learner determines where they are in relation to the learning target. I also love the fact that they can advocate for support from not one but two different teachers. Knowing Nicki and her incredible staff, what you see above is most likely the norm in many Quest Academy classrooms.

Try This

- First, if you’re already using exit tickets or some other means of lesson closure, that’s great, but take a minute to reflect on whether they’re providing the type of substantive info I’ve outlined here, or if they’re simply making your lessons slightly longer. Consider if your use of closure elements might be tweaked to provide greater value to you and to your students. As you approach future lessons, zero in on what these tasks are telling you about student learning—on an individual basis and as a whole group. Are you seeing any patterns? How might you adjust your instruction to provide more focus where each student needs it?

- If exit tickets are new to you, that’s great, too—what an opportunity! First, consider what feedback would be most helpful to you and your students. The example I provided here is just one, but Google “exit tickets” and you’ll see a number of examples. Don’t reinvent the wheel. Find one that fits your needs and modify it to make it yours. What lesson this week is a natural fit for an exit ticket? Choose one, develop your ticket, and just try it with your class. Then reflect on the information it provides—how does this align with your expectations around what you want your students to understand? What steps will you take to adjust your instruction? Remember, data is great, but it’s what we do with it that matters.

Great job Mrs. Hueftle! Definitely borrowing some of these ideas and hope to learn more about how you use exit tickets in science :)

ReplyDelete