‘What Do I Get If I Do It?’ The Cost of Rewards

By Dr. Debbie Silver

In response to the significant decrease in student motivation during the past two challenging years, many educators have chosen to explore different means to promote engagement – including rewards.

Teachers designed ingenious rewards to entice students to pay attention, participate in various teaching platforms and turn in quality work in a timely fashion. From digital reward tags to ClassDojo points to allowing extra game time, educators desperately sought ways to keep students “pumped up” for learning.

I understand the perceived need for coaxing reluctant learners to keep moving forward, but I wonder about the cost of using external motivators in place of encouraging intrinsic motivation.

And now that we are returning to face-to-face learning, how do we dial back our excessive reward systems?

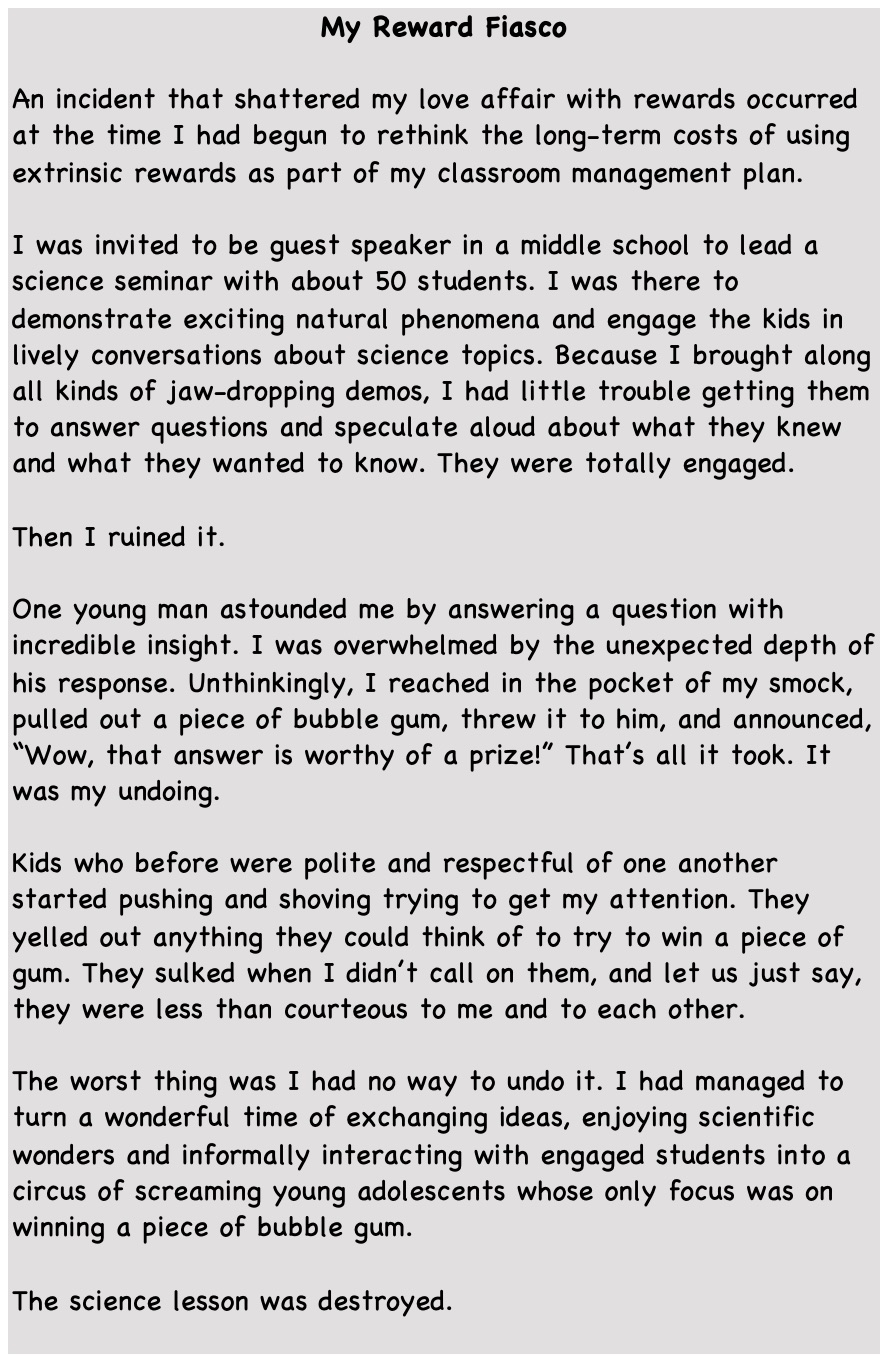

I Was That Teacher Too

I admit that I once was that teacher who used certificates, raffle tickets, class parties, and whatever I could think of to reward my students for making appropriate behavior choices.

I thought I was creating a positive classroom setting that benefited everyone, including me. I started having doubts about my system when it became apparent that many students were aggressively competing for certificates and points but weren’t necessarily internalizing the self-regulation and social skills I was trying to promote.

As I began to reexamine my fondness for external compensations, I did some research and found that extrinsic rewards basically fall into three categories.

- Task-contingent rewards are available to students for merely participating in an activity without regard to any standard of performance (e.g., anyone who turns in the assignment gets a prize).

- Performance contingent rewards are available only when the student achieves a certain standard (e.g., anyone who has at least 93% correct responses on the assignment gets a prize).

- Success-contingent rewards are given for good performance and might reflect either success or progress toward a goal (e.g., anyone who has at least 93% correct responses on the assignment or improves their last score by at least 10% gets a prize).

Task contingency is solely focused on compliance. “You do this, and I’ll do that.” No attention is paid to the quality of the job or the effort that went into the task. Unfortunately, this type of goal focuses only on student conformity and is often grounded in a covert bargain that they will get what they want if we get what we want.

Most researchers agree that task-contingent rewards are at best futile and at worst counterproductive. There are differing opinions about the need for either performance-contingent rewards or success-contingent rewards, but at least success-contingent rewards give everyone a reasonable chance.

Whichever carrots – with or without the sticks – we might choose, the question still comes back to, “Do rewards help students become better learners?”

Is It Ever Okay to Give Extrinsic Rewards?

The short answer is yes (sometimes). Teresa Amabile, professor at the Harvard Business School, has done considerable research on rewards and their effect on creativity. She and her colleagues have determined that an extrinsic reward can have positive impact if it is unexpected and offered only after the task is completed.

Giving someone a certificate of appreciation after they have designed the school’s logo as a congratulatory symbol of achievement has a different, more positive effect than making a task-contingent offer beforehand: “If you design the winning logo, you get this prize.”

Amabile and other experts recommend that adults consider keeping rewards nontangible when possible. Can feedback be described as a “reward”? Perhaps. Effective use of positive, constructive feedback is one of the most valuable means for fostering creativity and active involvement as well as nurturing intrinsic motivation. Our feedback needs to be honest, specific, nonjudgmental, and given for the express purpose of helping students get better at something.

► Effective feedback is based on an understanding of student interests and skills. We can make use of student surveys and conversations to better integrate student interests into classroom instruction and pointers.

► Effective feedback is used purposefully to improve student learning and performance. We can support self-efficacy and growth mindset if we use feedback to inform rather than to label, rationalize, or excuse. It is not always easy, but educators must get better at ensuring our feedback is always given in terms of things students can control. Comments about innate ability, luck, or the difficulty of the task direct students’ attention towards things over which they have no power rather than helping them focus on the things they can always control – their choices and their efforts.

► Effective feedback orients students toward better appreciation of their task-related behavior and thinking about problem-solving. “Do you realize you just exceeded your personal best record?” “Show me how you solved that difficult program.” “Let’s take a look at the progress you’ve made these past few days.” Students are primarily influenced by how well they have performed in the past. Significant adults in children’s lives can increase students’ confidence by helping them recognize past accomplishments. In this way, success breeds success. Helping students acknowledge past growth is an important contributor toward their future growth.

How Do We Make Feedback “Effective”?

It is essential to let students know we believe in them and their abilities. It’s equally important that we give them precise, constructive feedback that helps them to improve. Both what we say as well as how and when we say it are relevant to how effective our feedback is.

● Effective feedback is timely. In most cases, feedback needs to happen as quickly as possible. The closer the feedback is given to the completion of the task, the more meaning it has for the learner.

● Effective feedback is given with attentiveness. If we are giving verbal feedback, we owe the learner our undivided, focused attention. We get eye level with them and make sure to limit distractions for both them and us. If our feedback is in written form, we make sure it is legible and easy to understand.

● Effective feedback uses descriptive language. We use precise terms that leave little room for misinterpretation. Instead of using words like “good” or “super,” we try for illustrative phrases that more accurately convey our exact meaning (e.g., “Your paragraph used clear, concise words that vividly described your main character”).

● Effective feedback is positive. We let the learner know what they did well. Likewise, we let them know what they almost did well. We make sure our voice, our manner, and our comments indicate that we believe the learner can reach their goal.

● Effective feedback offers autonomy. We encourage the learner to offer their own ideas on how they can improve. We ask if they are ready to work on the suggestions we’ve brainstormed together. If they say, “No,” we ask them what they are willing to do. We let them know they have control over how much improvement they want to make.

● Effective feedback uses observations, not inferences. We use the student’s work to frame our comments. Inferences are the assumptions or opinions we have about an individual’s actions. It is not helpful to ascribe motives to another’s acts. We simply state what we saw or heard. Observations should be objective and factual. Only the learner knows why they made the choices they did.

● Effective feedback avoids feedback overload. Constructive feedback should not be overpowering. We know there will always be another opportunity to address points not covered in one session. Too much feedback at once can cause the learner to become disengaged, confused, or discouraged.

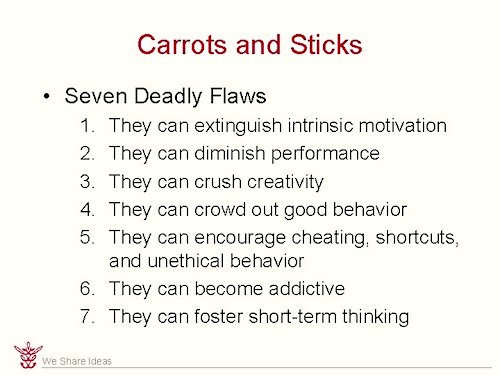

Effectual feedback drives intrinsic motivation. External rewards can extinguish the behavior we are seeking to encourage. A wealth of research confirms that excessive rewards have negative results. In his book, Drive (2009), journalist and social behavior researcher Daniel Pink explained that carrots and sticks (external motivators) have seven deadly flaws.

My Best Advice: Usually Less Is More

In his famous TedTalk The Puzzle of Motivation (2009 – 28M views), Dan Pink goes on to say that in some cases extrinsic motivation can be beneficial. Rewards, for example, can be effective for rule-based routine tasks where there is little intrinsic motivation to undermine and not much creativity to crush.

Pink also believes that recognition that confirms competence can be a valuable motivator. I am glad about that. I love praise when it is earned – both receiving it and giving it. Nonetheless, I think it may be time for us to evaluate whether educators’ use of extrinsic motivators, including praise, is our best choice when we are in a position to give regular, effective feedback – as teachers often are.

The use of rewards is a complicated issue that must be seriously considered and reconsidered by teachers. We don’t want our short-term objectives to circumvent the long-term goals we have for developing self-reliant, intrinsically motivated, responsible citizens.

I don’t believe there is a single right answer to how much, how often, or what kinds of rewards are appropriate for all learners. I still struggle with this issue. Nevertheless, my research and my experience have led me to believe that usually less is more. Sometimes the simple act of giving students our full attention is the most effective way to support them.

I am interested in your thoughts on the subject. Please use the comments section to state your position on the use of rewards in the classroom.

Reference

Amabile, T. and Kramer, S. (2012). What Doesn’t Motivate Creativity Can Kill It. Harvard Business Review April 25, 2012.

Debbie offers more information and resources on SEL and self-motivated learners in her recently released and extensively revised Fall Down 7 Times, Get Up 8 (2nd ed.): Raising and Teaching Self-Motivated Learners. (Corwin Press, 2021) Visit her website.