What you believe about intelligence affects how you teach

How we teach is an extension and a physical sign of our strongest beliefs, not only about how people learn but about humanity itself. It’s often said that “we teach as we were taught”. More generally, we teach as we believe.

We certainly tend not to teach in ways counter to our beliefs, even if there are data suggesting we should change. Take active learning as a major example. The evidence, both empirical and anecdotal, for active learning's superiority as a platform for teaching and learning is as close to settled science as we can get in education. The 2014 Freeman report alone should be enough to see that. And yet, the dominant form of instruction in higher education today is still lecture, even when instructors know what active learning is and what its benefits are.

If active learning is such a great idea, why are faculty still so reluctant to adopt it? This question is the focus of dozens of research studies and grant programs. These tend to focus on external factors such as the availability of training resources and connections to promotion and tenure. But one study I recently read brings the question back to beliefs: Specifically, the connection between pedagogical choices and faculty beliefs about intelligence.

Aragón, O. R., Eddy, S. L., & Graham, M. J. (2018). Faculty beliefs about intelligence are related to the adoption of active-learning practices. CBE—Life Sciences Education,17(3), ar47. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-05-0084

The paper is open access, and you can download it here.

What is this study about?

This study looks at beliefs about intelligence through the lens of fixed mindset versus growth mindset. Just in case you’re unfamiliar:

Someone with a growth mindset views intelligence, abilities, and talents as learnable and capable of improvement through effort. On the other hand, someone with a fixed mindset views those same traits as inherently stable and unchangeable over time. (Source)

It makes sense that a fixed or growth mindset would affect how you teach. If you believe that intelligence can improve through effort, then you would be drawn to active learning, because active learning is predicated precisely on students doing things to improve their intelligence. Likewise, if you believe intelligence is basically fixed, then why bother with active learning? Just get the information out there, and let students use their intelligence.

The study also views "adoption" of active learning through a specific model, called the EPIC-Implementation model. It states that the adoption of teaching practices flows through five stages:

- Exposure: First, faculty have to be exposed clearly to the teaching practice, through a paper, workshop, blog post, and so on.

- Persuasion: Then, faculty must be persuaded that the practice is a good idea generally speaking. Note, this may or may not have anything to do with supporting data.

- Identification: Then, faculty come to believe believe that the practice makes sense for them, personally, and not just a good idea.

- Commitment: Then, faculty engage in "preaction" by committing to using the practice in their work.

- Implementation: And finally, faculty actually start using the practice in their daily routines, and engage in feedback loops and iteration to improve over time.

Faculty movement through these stages is mitigated at every step by beliefs and attitudes. But how, and to what extent — especially when it comes to active learning and a fixed/growth mindset about intelligence? The main research questions for this study are:

- Is it actually true that faculty beliefs about fixed versus growth mindset have a significant effect on any of the stages of adoption in the EPIC-Implementation model? And,

- If so, in which stages do we find the greatest impact?

The authors predict that the answer to the first question is "Yes", and the answer to the second is "Persuasion":

Instructors with fixed mindsets may be less convinced that incorporating activities into their classes can help students improve, whereas instructors with growth mindsets may be more persuaded. In addition, we predicted that, because of lower persuasion, instructors with a fixed mindset would also be less likely to implement active-learning relative to instructors with a growth mindset.

Basically, if you don't believe intelligence can be changed, then you will be significantly less likely to think that active learning makes sense, and therefore less likely to actually use active learning.

What did the author(s) do?

The study focused on a group of college instructors who were graduates of a multi-day intensive training workshop on "scientific" (that is, evidence-based) teaching methods, over a period of several years. The overall pool of subjects was 1179 people, and eventually 620 participated. These were alumni who were still actively teaching and who completed a survey, which consisted of two parts.

One part consisted of questions about teaching practices, specifically 19 prompts focused on active learning, formative assessment, and inclusive teaching; seven of those 19 prompts were on active learning and were the focus of this study. The prompts themselves were in the form of a grid: Along the left side of the grid were the seven active learning practices, and each practice had five boxes to check: I was exposed to this, I was convinced this is good, This is compatible with my teaching, I made a decision to incorporate this in my teaching, and I implemented this practice in my course. Respondents were told to check all the boxes that apply.

The other part of the survey contained three Likert-scale questions about beliefs regarding intelligence: I believe that you have a certain amount of intelligence and you really can't do much about it; I believe that your intelligence is something about you that you can't change very much; and I believe that you can learn new things, but you can't really change your basic intelligence. Respondents rated each of these 1 (strongly disagree) through 6 (strongly agree). The scores on each were averaged to create a single score that, as you can guess, gives a measure of belief in fixed versus growth mindset.

What did the study find?

The summary statistics from the survey are themselves pretty interesting. For example, the mean for the "mindset score" above was 2.84 (standard deviation of 1.27), which (if you believe in averaging Likert scale scores, which is something I'm not so sure about) indicates a general tendency toward a growth mindset --- but not an overwhelming one. In fact over a third of the respondents generally aligned with a fixed mindset about intelligence, which I found surprisingly high given that the respondents were alumni of an intensive workshop on scientific teaching practices in which they (presumably) voluntarily participated, which you might think would skew heavily toward growth-mindset types.

But the main use of the data was to create a model that relates the level of adoption of the seven active learning practices in the survey to the mindset score. You probably noticed that the five boxes that respondents checked in the grid are exactly the five stages of the EPIC-Implementation framework. So it's possible to build a regression-flavored model that correlates the mindset score with each level of EPIC-Implementation, both to see whether beliefs about intelligence have any significant impact on the adoption process, and if so, where this occurs most strongly.

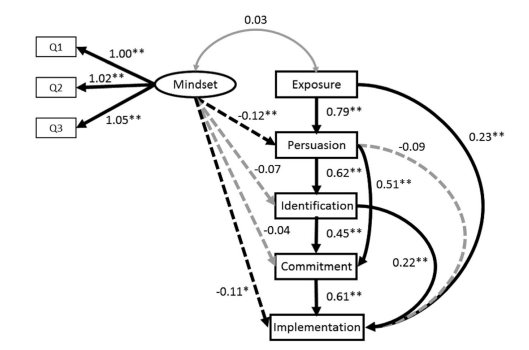

The main predictions of this study were that fixed/growth mindset beliefs will have a significant impact on active learning adoption, particularly at the "Persuasion" stage. The data confirmed that prediction with a statistically significant correlation between the mindset score and two stages of the EPIC-Implementation framework: Persuasion and Implementation, with the mindset-Persuasion link being the stronger of the two. The study found that a 1 standard deviation increase in mindset score (which would mean a movement toward the fixed-minset end of the Likert scale) was associated with a 0.12 standard deviation decrease in the rate at which respondents were persuaded by a teachign method. (Recall that the prompt for Persuasion was "I was convinced this [teaching method] was good".)

As a bonus, although it's not part of the main research questions here, the data can also reveal correlations between the different levels of the adoption process. You'd expect to see significant correlations between consecutive stages, for example between Exposure and Persuasion or Commitment and Implementation, and those did occur. But interestingly, the data also show a significant correlation between non-consecutive stages. In particular there was a strong positive correlation between Persuasion and Commitment (skipping over Identification); and between Identification and Implementation (skipping Commitment) and Exposure and Implementation (skipping everything).

The various connections and their statistical strength are summed up in this figure from the paper. The bold arrows represent statistically significant correlations and the numbers are the correlation coefficients.

What does it all mean?

There does appear to be a connection between your belief about intelligence in the one hand, and how persuaded you are likely to be that an active learning practice is a good idea generally speaking, and how likely you are to actually implement such a practice, on the other. Simply put, the more you tend toward a fixed mindset, the less likely you are to think that active learning practices make sense. You'll also be less likely to implement one of those teaching practices in your own classroom --- perhaps because you're not persuaded, but perhaps even if you are.

I think that this connection goes both ways. Our beliefs and attitudes affect what we do, but what we do tends to reinforce our beliefs and what we allow ourselves to be persuaded about. I think those who teach with active learning regularly do so because we are persuaded, not by research data but by the practical outcomes that we see in the classroom through implementing those practices. Likewise, if you teach with a more passive style, you're likely to become entrenched in a fixed mindset, because that's what your teaching is set up to show you.

What all this suggests is that maybe the best way to persuade someone to use active learning is to have a conversation about what they believe regarding intelligence. I recently wrote that giving research data to skeptics of teaching innovations is likely to backfire because people, even people with Ph.D.s, tend to make decisions not based on data but on what they believe (and because of inertia).

This goes for students as well as faculty! If you, as an instructor, get pushback from students about your use of active learning, then rather than digging in or throwing the Freeman paper at them, consider giving students those three mindset questions from the study to see what their beliefs are, and then discussing the results as a class. I would wager that most students today have a fundamentally growth-mindset outlook on intelligence – perhaps moreso than even the faculty in the study. In that case, leverage their innate beliefs and ask questions like, If you think intelligence can be improved, which use of class time does a better job of that: Lecture, or active learning? That's a line of inquiry that might get students to trust you.

Finally, in this study I am seeing some weaknesses in how we currently do faculty development. Our approaches on this front seem to focus only on the "E" and the "P" of the EPIC-Implementation model --- mostly "E". We bring faculty into a workshop or a keynote and expose them, good and hard, to best practices in teaching... and then stop. Now, a good workshop or keynote will attempt to persuade faculty. But it's rare in my experience to see faculty development sessions aim toward getting commitments out of faculty, even rarer to get those commitments and then walk alongside faculty as they implement. Asking for commitments smacks of evangelism, or worse, "telling people how to teach". But merely exposing people to a concept and then assuming it will magically metastasize into implementation, seems like the exact opposite of active learning practices themselves. I'll be pulling some more on that thread in a later post.