Grow a Love for Reading with an Ocean of Books

Author, teacher, coach and speaker Laura Robb has championed the idea that reading and access to books is a civil right throughout her celebrated career. In this story of turning around reluctant readers far below grade level, she makes a powerful case that when kids have lots and lots of book choices and plenty of time to read in and out of school, they’ll become readers for life.

For three consecutive days I had conversations with 25 fifth grade students who were entering an area intermediate school reading at a kindergarten to first grade instructional level.

Our discussions included exploring students’ interests outside of school, getting to know their families, and discovering their feelings toward reading. My job was to train ELA teachers and develop a curriculum to meet all students’ needs and that included the two dozen students reading far below grade level.

“I hate reading.”

“It’s boring.”

“You’ll never make me like to read.”

Student comments like these echoed through the room every time I asked, “How do you feel about reading?” At first, like me, you might bristle each time students spoke such words, for deep in our teaching hearts you and I always hope that our students will love to read.

Their responses left a trail of frustration and disappointment within me. However, I quickly recognized that I had to move beyond students’ comments and explore ways to help these developing readers – students reading three or more years below grade level – move forward and enjoy reading.

Once I pushed aside my frustration and disappointment, I was able to credit students with being honest and then spend my time figuring out ways to assist and sustain their reading growth.

A Curriculum That Works

The principal provided funding to add lots more books to school and classroom libraries and adjusted students’ daily schedule. Fifth grade ELA teachers and I created a curriculum that enabled all learners to make significant progress. Beside ninety minutes in ELA classes, our group of two dozen hardened non-readers worked with me an additional hour every day.

ELA teachers opened class with fifteen minutes of independent reading followed by a teacher read aloud. Instructional reading and notebook writing about reading occurred in homogenous groups, and developing readers read informational books and biographies. Class ended with students practicing reading a poem they selected out loud to a partner, and at the end of the week, volunteering to read their selected poem to the class.

My sixty minutes with students opened with a short teacher read aloud followed by twenty minutes of word sorting (We used Words Their Way) and students kept a word study notebook with completed sorts and related words. The remaining time was for independent reading.

Frequently, I modeled how to choose a book, referring to a chart with guidelines for choosing a “good fit” book. Gradually, students learned to self-select books they could read and enjoy. Thanks to district and school funding, ELA teachers and I had classroom libraries and extra funds to purchase books that met students’ continual progress and growth in reading.

Authentic Reading Experiences

In my sessions students read authentic, outstanding books with photographs and illustrations that stirred their interests, enhanced their background knowledge and offered opportunities for analytical thinking and character exploration.

Books and reading in their ELA class and in my intervention class were the heart and soul of our curricula: teacher read alouds, twenty minutes of instructional reading, forty-five minutes of independent reading of self-selected books, plus twenty minutes of independent reading at home.

By increasing the amount of daily independent reading, students ramped up their reading volume and began inching forward (Allington, 2014). By the end of fifth grade most developing readers made one to two years progress. Yes. Volume in reading mattered!

What We Know about Independent Reading

There is a close connection between the amount of independent reading of self-selected books students complete, reading achievement, and their ability to comprehend challenging materials.

Research supports the benefits of independent reading. In 2004 a scientific study completed by researchers Samuels and Wu pointed to a strong correlation between students’ reading achievement and the volume of reading resulting from reading self-selected books.

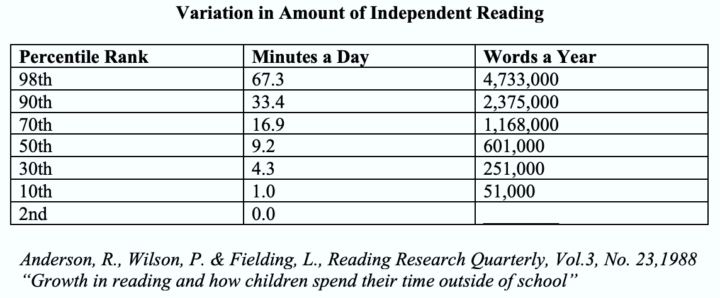

In 2020 Finland conducted an extensive study that examined the independent reading of 2,525 students from age 5 to 15. The study concluded that independent reading promotes reading development and achievement. Both studies also validated an earlier research project completed in 1988 by Anderson, Wilson, and Fielding.

Reading volume is the combination of the time students spend reading plus the number of words they actually read. This combination affects students’ cognitive abilities and cultivates an enthusiasm for reading.

The chart shows the growth of students’ reading skill and vocabulary depends on the amount of independent reading they do. Samuels and Wu’s study identified forty minutes of independent reading at school as the research-based ideal amount of time.

Some Conclusions from the Data

Independent reading of self-selected books builds:

- reading, speaking, thinking, and writing vocabulary;

- background knowledge;

- an understanding of diverse genres;

- comprehension of new concepts;

- literary language;

- reading stamina;

- literary tastes;

- the ability to read like writers; and

- supports students becoming lifelong readers.

Nancie Atwell also links daily reading to improving and increasing proficiency in reading books (2010). Volume in reading is an effective intervention for developing readers (Allington 1977, 2012, 2013; Allington & Gabriel, 2012) and a predictor of learning success because students who read, read, read perform better on standardized tests in reading, vocabulary, and writing than students who read little to no books.

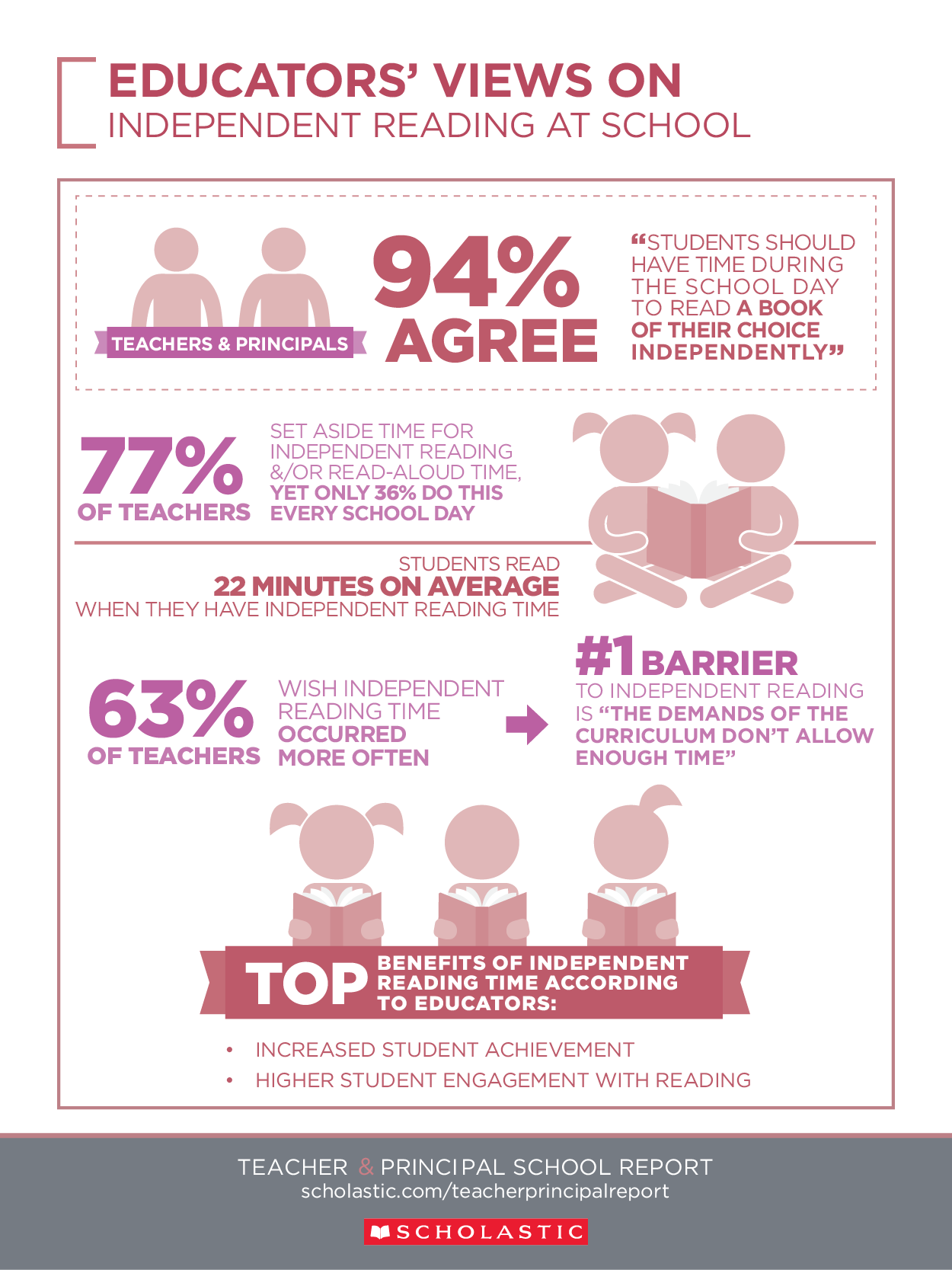

Sadly, the reality is that research data reveal students aren’t reading enough. Studies by Scholastic of the amount of reading students do at school and at home correlate with the flat trend in reading scores on our nation’s report card, the National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP), from 2009-2019.

- Daily in-school independent reading occurs for 17 percent of students, ages six to seventeen (Scholastic 2015).

- By age nine, reading volume starts to drop: 35 percent of nine-year-old children report reading five to seven days a week compared to 57 percent of eight-year-old children (Scholastic, 2019).

- Since 2009 there has been a steady decline of children reading nearly every day, and a rise in those reading less than one day a week (Scholastic, 2019).

- Survey findings based on nearly 3,700 PreK-12 teachers and librarians show that 94% of principals and teachers agree or strongly agree that students should choose books at school and read independently every day, but only 36% made time for daily independent reading (Scholastic, 2017).

This drop in time students read independently at school can have a negative effect on students’ literacy development and ultimately result in disengagement with reading due to a lack of daily practice (Allington,1977, 2012, 2013; Goldberg & Houser, 2020; Miller and Sharp, 2018; Robb & Robb 2020).

Access to books and time to read at school every day classes meet can foster engagement with reading, increase volume in reading, and can lead to students developing a personal reading life.

How Do We Assess Independent Reading?

Asking students to complete a project on every book they read punishes those whose reading mileage is high and also removes joy from reading. Instead, try the two suggestions below that encourage students to share books. Remember, there’s no need to monitor every book students read.

Informal Book Shares

Sharing is ungraded and can occur every six to eight weeks. The purpose is for students to share a book and say why they enjoyed or abandoned it. Set aside fifteen minutes of a class, organize students into groups of four and invite them to select a book to share from their reading log lists. Create different groupings each time students meet for book sharing. Ask students to have their notebooks ready to jot titles of books they might want to check out.

Student Book Talks

In my classes, students commit to a short book talk each month. Sometimes I select a book from their list; other times they choose. You can grade these as long as you set specific guidelines for students to follow.

It’s helpful for you to prepare notes for a book talk of your own on an index card and then present the short talk modeling how you elaborate on notes. Doing this enlarges students’ mental model of a short but informative book talk.

Set aside two days near the end of the month and have half the class present on each day. Or you can invite students to let you know when they’re ready to present and sprinkle book talks throughout the month. When a class of twenty-five students book talks each month, in ten months they will learn more about 250 books. That data, combined with book talks you and the media specialist present, can introduce students to more than 300 books. Moreover, there’s great power in peer-to-peer reading recommendations!

Book Talking Tips For and By Students

Students should plan their first book talk during class and rehearse it with a partner. This allows you to answer questions and provide feedback. Possibilities are wide-open with the exception of retelling the book – giving away the entire book is boring and can diminish students’ desire to read it.

The goal is to leave listeners wondering, wanting to learn more, and eventually checking out the book. Remind students to bring the book and briefly share and discuss important points featured in the title and cover illustration. Invite them to open their book talk by stating the genre and a two to three sentence summary that piques peers’ interest.

Five Student Ideas for Book Talks

What follows are students’ suggestions I’ve collected. You can use these, but also consider inviting students to add ideas to the list.

- Find a short quote from the book that spoke to you. Share the quote by writing it on a whiteboard, explain why it resonated with you, and how it connects to a theme in the book.

- Share a cliffhanger and how it made you feel and react. If the book has lots of cliffhangers, include this in the book talk.

- Identify the protagonist and show how they changed from the beginning to the end of the story. Include one event and one character that caused the protagonist to change in some way and explain what happened.

- Explain one way the book changed your thinking about the topic.

- Explain why you disliked a book and why you didn’t abandon it.

Some Closing Thoughts

Reading is like a sport. To become better soccer, tennis, basketball, or volleyball players, teams practice to develop automaticity of moves, to rehearse winning plays, and to improve overall skill.

To help students become better readers, increase volume through independent reading, so they develop automaticity of word recognition, enlarge background knowledge and vocabulary, apply high order reading strategies, and become critical thinkers.

The ultimate goal is to become skilled readers who fall in love with reading. The research is conclusive: independent reading of self-selected books builds the volume in reading that can help every student reach this goal.

Robb presently coaches teachers in grades 5 to 8 in Virginia and North Carolina. In addition, she is a consultant for Penguin Random House’s education division and has developed culturally relevant classroom libraries for grades PK to 8.

Robb has received NCTE’s Richard Halle Award for excellence in middle level education and presently directs her energy to explaining why volume in reading and access to the finest inclusive books is a civil right of all students She is a regular contributor to The Robb Review Education Blog including a series of podcasts with principal and son Evan Robb.

I am curious, at the school where you worked with these 25 students, was there a full-time, certified teacher-librarian on staff? You mentioned librarians a couple of times in your post, but what do you see as the role of a full-time, certified teacher-librarian in a school as it pertains to interest in reading and access to a wide (beyond classroom-library) variety of professionally reviewed reading material?

Hi Dianna, That school has a certified librarian and of course, the media center’s collection far exceeds the amount of books in a classroom library.A certified librarian is extremely knowledgeable about books–far more than the classroom teacher.

Librarians support the units of study in ELA and content classes as well as help students with research, passion projects, PBL, and finding books that capture their imagination. Wearing a variety of hats, the librarian also advises teachers on adding books to their classroom libraries, holds annual book fairs, informs teachers of new books and materials, and helps create a culture of reading in a school.

I have introduced a 15 minute block of reading time to the beginning of each of my Humanities lessons (75 minutes each) with Year 7 students. I have found this to be an effective way to not only encourage a love of reading but also help students to regulate after breaks. They have enjoyed the routine and feel more ready to learn after reading.

Hi Tracey, Your findings totally align with my experiences and with teachers I coach who start their ELA classes with 15 to 20 minutes of independent reading of self-selected books.

You’re spot-on when you observe that it helps students regulate after breaks and that they’re ready to learn after reading. They also develop stamina–the ability to concentrate on their reading for extended time as well as discover authors and genres that they love.

I also find that for me it’s a peaceful and joyful time as I can read as well as occasionally confer with one or two students. Spread the word to your colleagues!