Learning About Young Makers

I am a huge proponent of using hands-on, interactive learning activities to explore ill-defined problems as a way of teaching for all age groups. Given the spontaneity and uncertainty of these types of active learning environments, I believe educators should observe, reflect on, and analyze how learners interact with the materials, the content, the educator, and the other learners. This practice is in line with the teacher as ethnographer.

In my role as a teacher as ethnographer, I made some initial observations during my first two weeks of teaching maker education for elementary age students. With half the kids under 7, I learned a bunch about young makers.

- Young makers are more capable than what people typically believe.

- Young makers need to be given more time, resources, strategies to learn how to solve more ambiguous and ill-defined problems (i.e., ones that don’t have THE correct answer). Too many don’t know how to approach such problems.

- If a project doesn’t “work” during the first trial, they way too often say “I can’t do this.” They have a low tolerance for frustration; for not getting the answer quickly.

- Young makers often celebrate loudly and with extreme joy when making something work.

- Young makers like to work together but lack skills or desire to peer tutor one another.

- Young makers usually like to stand while working.

Young makers are more capable than what people (adults) typically believe.

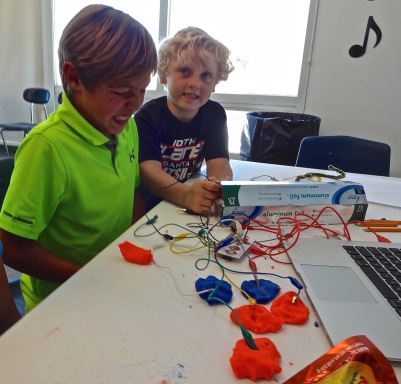

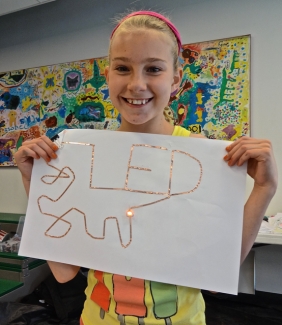

During our maker education summer camp, the young makers made LED projects, circuit crafts, and simple robotics. Looking at the instructions for similar activities, the recommended ages were usually 8 and above. Yet, my group of 14 kids contained half under that age. The kids of all ages struggled a bit – as is common with making type activities but all were successful to some degree with all of the activities.

I believe that children are way too often limited by our (adults’) expectations of what they can and cannot do rather than what they actually can understand and do.

I think we often talk down to children and we think they’re not capable of deeper understanding, and I think that’s false. So we treat them like they’re capable human beings and we use scientific terms and talk to them in a way that they can gain knowledge from those things (Young Learners STEAM Ahead).

If a project doesn’t “work” during the first trial, they way too often say “I can’t do this.” They have a low tolerance for frustration; for not getting the answer quickly.

The nature of maker education is that makers engage in activities that require experimentation, trial and error, and multiple attempts. This is not the norm for kids in mainstream education environments. The curricular activities, worksheets, and tests of our current education system most often include single attempts and then assessments on degree of correctness. Multiple attempts and mastery learning of individual learning activities are not the norm. Life is not filled with getting single correct answers yet we are giving kids an education that there are.

During our maker education weeks, if a project didn’t work on the first attempt, many of the young makers would exclaim, “I can’t do this.”

One young maker, a 3rd grader, was obviously intelligent and easily jumped into the maker activities. For each of the learning activities, he would try it and more often than not, that activity wouldn’t work correctly the first trial. He would then quickly find me and tell me that activity didn’t work. I asked him if he was used to things working the first time and he responded that they did work for him the first time. Instead of helping him solve the problem, I told him to go work it out for himself. He looked at me with a frustrating and somewhat angry look but each time he went back to that activity and would make that activity work.

The maker education activities help learners discover that perseverance pays off but the educator must let the learners struggle giving them the message that effort often produces positive results. This supports a growth mindset.

In the following video, Carol Dweck talks about making challenge the norm when working with our learners.

Young makers need to be given more time, resources, strategies to learn how to solve more ambiguous and ill-defined problems (i.e., ones that don’t have THE correct answer).

Related to the “I can’t do it”, many of the young makers struggled with the strategies needed to solve more ambiguous and ill-defined problems. For example when a circuit or a robotic component didn’t work, they looked to me to resolve the problem for them. Although, I was tempted to go solve it for them, I knew that wasn’t in their best interest. I would say things like, “Give it another try,” ” Try something different,” and “Ask another learner for help.”

Problem-solving is, and should be, a very real part of the curriculum. It presupposes that students can take on some of the responsibility for their own learning and can take personal action to solve problems, resolve conflicts, discuss alternatives, and focus on thinking as a vital element of the curriculum. It provides students with opportunities to use their newly acquired knowledge in meaningful, real-life activities and assists them in working at higher levels of thinking (Problem Solving).

Young makers often celebrate loudly and with extreme joy when making something work.

There is nothing in the world as magically as watching a young person’s face light up when s/he understands a new concept, gets something to work that hadn’t at first, or discovers something new and exciting. It is those light bulb moments. There were lots of exclaims of “I did it” during the maker activities. These exclamations were especially joyful given that they often struggled in making their projects work (as previously discussed). The joy in their voices and in their faces during those moments cannot be matched and maker education provides lots of opportunities for those moments.

Giving students time to figure things out for themselves without being instructed, is very powerful learning. They will remember it for the rest of their lives. Students need that kind of lightbulb learning – that Eureka! moment when they suddenly realize something new for the first time (Lightbulb Moments)

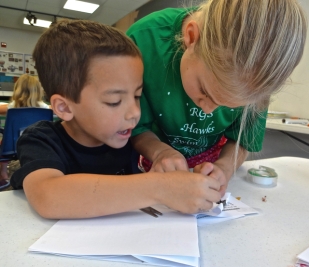

Young makers like to work together but lack skills or desire to naturally tutor one another.

As is characteristic of maker activities, some of the kids completed the activities faster than the other kids. One of my themes during the maker education weeks was that if you understood and finished your project quicker than those around you, that you should help them. They would happily help whenever I asked them to but it never came naturally. I had to continue to ask throughout the weeks. Then, at times, they would help for a minute or two and then stop.

I understand that part of the reason is the developmental nature of younger kids who tend to be more egocentric but I also believe that it is because they aren’t being given the message and opportunities to help fellow students in the more formal classroom.

Giving students the opportunity to practice prosocial behavior is one of the most effective ways to promote it. For example, when having them work in cooperative learning groups—an instructional technique that allows small groups of students to work together on a task—inform students that part of their responsibility as members of the group is to help one another. Scientists have found that students who engage more in cooperative learning are more likely to treat each other with kindness. (Four Ways to Encourage Kindness in Students)

Young makers often stand while working.

Throughout my weeks with the young makers, they always had a chair available to sit to work. Choosing to sit or stand while working was not an option that was overtly stated. Many, though, chose to stand.

The reason this is being mentioned as part of this post is that sitting quietly in one’s chair is the expectation of most schools. Why? It is often not learner’s first choice and sitting at a desk all day may be physically and mentally detrimental. The idea of standing in the classroom was recently addressed in several articles, Should Your Kids’ School Have Standing Desks? and How Standing Desks Can Help Students Focus in the Classroom.

Conclusion

Even though these weeks were considered a maker education summer camp, there was an expectation from the school and parents that the learning activities incorporated the expectations and rigors of a classroom environment. I could easily identify cross-curricular state and common core standards even though I never taught to THE standards. Never during the sessions were the young learners formally testing, asked to be quiet or sit still, or asked to finish quickly so we can move on. Yet, I believe each of the kids would say that they learned lots . . . . and had fun doing so.

Instead, the making learning activities were structured to honor natural ways of learning along with developmentally appropriate practices. Sadly, it appears that some of these natural ways of learning were “conditioned” out of the young learners through more formalized education as I identified in my observations. Incorporating making into a learning environment teaches lifelong learning skills such of perseverance, love of learning, working with others, and embracing challenges.

Written by Jackie Gerstein, Ed.D.

June 21, 2015 at 1:00 pm

Posted in Education, Maker Education

Tagged with 21st century skills, disrupting education, growth mindset, maker education, social learning

2 Responses

Subscribe to comments with RSS.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

worth reading

deborachaterins

June 22, 2015 at 5:37 am

Reblogged this on adventuresinleadingandlearning and commented:

Love this post by Jackie Gerstein!

shelleytbrett

June 22, 2015 at 7:02 pm