In our book UDL and Blended Learning, Dr. Katie Novak and I encourage teachers to work toward firm, often standards-aligned, goals. We also stress the importance of providing students with flexible means. All students can make progress toward firm goals, but they may need to take different paths to get there. Some students will move more slowly and benefit from additional support, scaffolds, and signage to get to the desired destination. Others will make the journey more quickly with significantly less help.

As we design learning experiences, one way to provide students with flexible means is to give students agency.

- What decisions will students get to make in the learning experience?

- How can we design meaningful choices that allow students to select a pathway that moves them toward the desired outcome?

When we build student agency into a task or an assessment, students may produce various artifacts to demonstrate their learning. They may express and communicate what they know or can do in different ways. The variety of products they create causes many teachers to question how they should assess this work since it takes many forms.

Let’s say the objective of a learning cycle is to help students to craft a strong argument, compare and contrast a plant and an animal cell, or use the formula for volume to solve real-world math problems. These are firm goals that all students can be working toward; however, the way they engage with information, the level of teacher support they receive, the time it takes them to reach the objective, and the product they submit may be different.

Let’s take a look at an example. If the learning objective is for students to craft a strong argument, you can provide them with different levels of support and different ways of demonstrating that skill. You can allow them to write an argumentative essay, 2) prepare and engage in a live debate with a classmate, or 3) record an argumentative speech. Not only can students select from these three avenues to demonstrate their learning, but you can also provide student agency in relation to the topic. Instead of assigning all students a single subject or issue to focus on for their argument, you can provide a list of topics and encourage students to select one of interest.

Example: Craft a Strong Argument

Providing students with multiple options may feel overwhelming, but using a single rubric to assess those products may make giving students a choice feel more manageable. Even though students might focus on different topics and produce different products to demonstrate their learning, we can use the same rubric to assess their skills if it is standard aligned.

Designing a Standards-aligned, Mastery-based Rubric

First, when designing any learning experience or learning cycle, I encourage teachers to identify target standards or skills that will frame and focus their design work.

Second, once they have their target standards or skills, we craft clear learning objectives. What will students understand or be able to do at the end of this learning experience or cycle? The learning objectives are what we want to assess progress toward. Whatever students produce or create should help us assess progress toward those learning objectives. If we are crystal clear about the outcome at the beginning of the design process, that creates clarity about what students will need to reach that objective successfully.

Step 1: Unpack your target standards or skills to identify the essential criteria you’ll assess. I encourage teachers to limit the criteria they include in their rubrics to avoid overwhelming students. For the example above, the criteria might include:

- Makes clear claims

- Presents relevant and compelling evidence

- Supports claims with valid reasoning and clear explanations

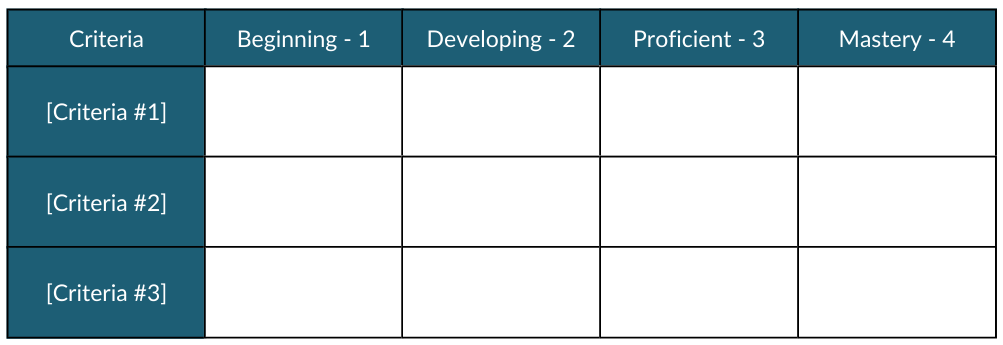

Step 2: Use a simple 4-point mastery-based scale.

- 1 = Beginning

- 2 = Developing

- 3 = Proficient

- 4 = Mastey

I share the template below with teachers to use in training sessions.

Step 3: Describe what you would expect to see at each level of mastery. What does it look like in the beginning stage versus the developing, proficient, or mastery stages? Writing these descriptions is the most challenging part of designing a standards-aligned rubric. It takes time to articulate what each level looks like; however, the benefit of this approach is that you do not need to write clarifying feedback. Students can read the descriptions to understand why they are receiving a particular score.

Suppose you align the criteria with the learning objectives you crafted from your target standards. In that case, you can use this one rubric to assess each product (e.g., argumentative essay, live debate, or recorded speech). If students are writing an essay, you might be tempted to evaluate mechanics or writing style; however, those are specific to that product and are not target learning objectives for this learning experience or cycle.

Regardless of whether you are giving students agency using a choice board, choose your learning path adventure, or a would you rather option, you can use a standards-aligned rubric to make sure you stay focused on assessing specific standards and skills at the heart of the learning experience.

The beauty of a standards-aligned, mastery-based rubric is that it:

- can be used to assess a variety of products in relation to specific criteria.

- reduces the time teachers spend grading because they simply mark the language on the rubric and do not have to write additional feedback to justify a score.

- provides students with a vehicle to understand their progress and level of mastery.

- can also be used as a self or peer-assessment tool.

You can learn more about universally designing blended learning to give students more agency in my book UDL and Blended Learning or by taking my online, self-paced courses.

3 Responses

I think that my son, would greatly benefit, from this approach. He is neuro-diverse, on the spectrum and has been struggling immensely with school. Being as clear as possible, about expectations and then showing him what he knows, (or at least, what he has shown you, he knows), could be a big motivator. I think he thinks school is pointless and doesn’t understand why, he’s constantly being asked questions.

How might you transition this approach into student success on a written assessment, like a district benchmark or state mandated test?

Hi Bonnie,

If the district benchmark is a one-size-fits-all approach to assessing writing skills, then you may not have control over how students communicate their ideas. A state-mandated test is also an example of something that you likely have no control over and you are not assessing.

I’d begin this work with the assessments you design.

Catlin