Part V: Thinking About Thinking Series

This is part five of a five-part series focused on using thinking routines to drive metacognitive skill building. Click here to revisit my last blog in this series on using the “Claim-Evidence-Question” routine.

To recap, metacognition is a cognitive ability that allows learners to consider their thought patterns, approaches to learning, and understanding of a topic or idea. Teachers can leverage the power of thinking routines developed by Project Zero at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education to help students develop their metacognitive muscles. The thinking routines are a collection of purposeful and structured thinking patterns designed to stimulate students’ cognitive engagement and cultivate higher cognitive awareness.

Teachers can use these thinking routines to design online or offline stations in a station rotation or embed them into a playlist to encourage students to pause and intentionally spend time thinking about their learning. Thinking routines offer more than just a structured pathway for students to delve into their thinking and explore the content deeply; they also serve as a window into their cognitive processes, offering invaluable formative assessment data.

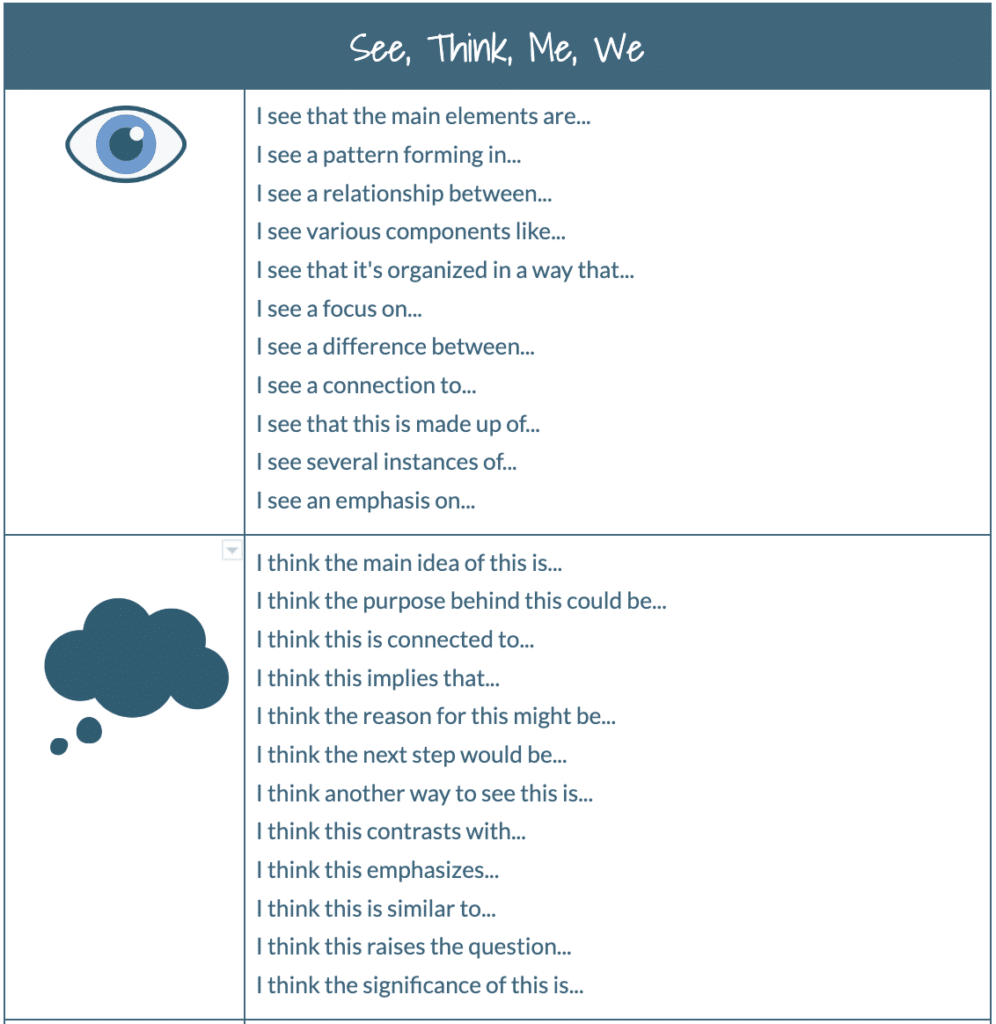

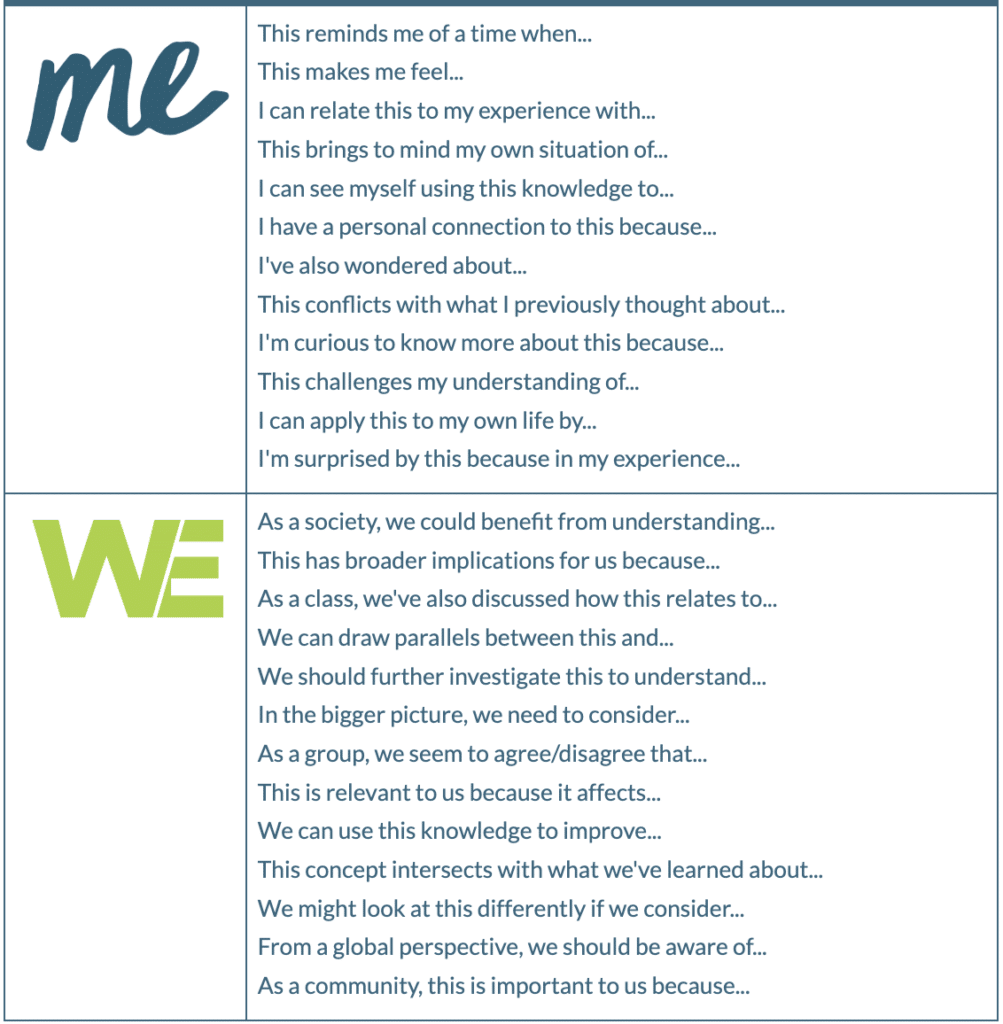

I See, Think, Me, We Thinking Routine

The “See, Think, Me, We” thinking routine promotes deeper understanding and encourages discussion. This routine aims to scaffold the thinking process by breaking it down into manageable chunks, thereby facilitating rich classroom conversations or introspective thinking. The routine can be applied to various situations, from analyzing a piece of art to discussing a historical event.

In the see phase, students are encouraged to make objective observations about what they see in front of them. This could mean describing the visible aspects of an image, identifying key elements in a text, or noting particular occurrences in a real-life situation. The goal is to collect as much raw data as possible without making judgments or interpretations.

In the think stage, participants move from observation to interpretation. They think about what these observations might mean, offering explanations, hypotheses, or interpretations. This is where analytical thinking comes into play. It’s a move from “What do I see?” to “What do I think about what I see?”

The me phase asks participants to reflect on their personal connection to what they’ve observed and thought. Questions in this phase could include “What does this remind me of?” or “How does this connect to my own experiences, ideas, or feelings?” The focus here is on introspection and personal relevance.

Finally, the we stage encourages participants to think about their observations, thoughts, and feelings in a broader social context. This could mean considering how a community or group (which could be as small as the classroom or as large as humanity) would perceive the subject or how it might affect or be affected by it. The aim is to promote social thinking and consider multiple perspectives.

By moving through these four phases—See, Think, Me, We—participants engage in a comprehensive thinking process that takes them from initial observation to personal connection and social relevance. Teachers often use this routine to deepen students’ engagement with material and to foster complex, critical thinking skills.

Using See, Think, Me, We…at the Elementary Level

Analyzing a Picture Book

See: The teacher shows an illustration from a picture book and asks the children what they see. Students might point out elements like the characters, objects, or actions taking place in the picture.

Think: The teacher then asks students what they think is happening in the picture. Students might say, “I think the girl in the picture is sad because she is sitting alone,” or “It looks like they are setting up for a birthday party.”

Me: Next, the teacher can ask how the picture makes the students feel or if it reminds them of anything in their lives. A student might say, “The picture reminds me of my birthday last year,” or “I feel happy when I see the balloons.”

We: Finally, the teacher asks how this picture might be important to other people, families, or communities. Students could discuss topics like the importance of friendship or how birthdays are celebrated differently in various cultures.

Studying a Historical Figure

See: The teacher presents a portrait or image of a historical figure. Students describe what they see: “He’s wearing a hat,” “She has a serious face,” etc.

Think: The teacher asks students to think about what kind of person this might be based on the image. They can discuss the historical figure’s potential characteristics or importance.

Me: Students are then encouraged to relate this historical figure to their lives. “Does this person remind you of anyone you know?” or “How would you feel if you met this person?”

We: In the final phase, the teacher asks how this person might have impacted a community, country, or the world. This can lead to a discussion about the figure’s contributions and larger impact.

Exploring Natural Phenomena

See: The teacher asks students what they see when they look at a diagram or model of the water cycle. Students might note clouds, rain, rivers, etc.

Think: Students are then asked to think about how these elements interact with each other. “What happens to the water after it rains?”

Me: In this phase, students could discuss personal experiences with rain, like jumping in puddles or seeing a rainbow.

We: Finally, the class could discuss broader implications like the importance of the water cycle for life on Earth or how communities are affected by weather patterns.

Introduction to Fractions

See: The teacher displays shapes divided into equal parts, some of which are shaded. Students are encouraged to observe these shapes and identify elements like the number of divisions and shaded portions.

Think: Next, the teacher prompts students to think about the mathematical concept represented by the divided and shaded shapes, guiding them toward understanding that these represent fractions of a whole.

Me: Students relate this concept to their personal experiences, such as sharing a food item equally among friends or family members, thereby connecting the mathematical idea to real-life scenarios they have encountered.

We: Students think about the broader importance of understanding fractions. This could include discussions about how fractions are used in various professions, such as cooking or construction, or how understanding fractions contributes to fairness and equity in sharing resources.

Using See, Think, Me, We…at the Secondary Level

Literature and Language Arts

See: Students identify key elements in a pivotal scene from a novel or a specific stanza from a poem, such as characters, actions, or descriptive language.

Think: Students consider the themes or emotions conveyed, speculating on the author’s intentions.

Me: Students relate the scene or poem to their experiences, discussing how it evokes personal feelings or memories.

We: The class explores the cultural or historical significance, discussing the work’s impact on society or a particular community.

History and Social Studies

See: Students analyze details of a primary source, like a historical letter or photograph, including date, author, and content.

Think: Students speculate on the source’s historical context and what it reveals about that period.

Me: Students connect the source to their own lives or current events, discussing its resonance or impact on their understanding of history.

We: The class considers broader implications, like how the source affects our collective understanding of history or current viewpoints.

Science

See: Students observe critical components in a scientific diagram or a physical demonstration, such as cellular respiration or the water cycle.

Think: Students discuss how these components interact and what they signify in scientific terms.

Me: Students relate the scientific concept to personal experiences, like how cellular respiration is related to exercise or the water cycle to their local climate.

We: The class debates the broader implications, such as how understanding the concept impacts healthcare or environmental policy.

Math

See: Students identify variables, coefficients, or other mathematical elements in an equation or graph.

Think: Students consider the real-world problem or mathematical relationship that the equation or graph represents.

Me: Students share personal experiences where similar mathematical problems or reasoning were encountered.

We: The class discusses wider applications of the concept in fields like engineering or economics and its societal impact.

Art and Music

See: Students identify elements like color, form, or melody in a painting, sculpture, or piece of music.

Think: Students discuss the mood, themes, or messages they interpret from the artwork or musical piece.

Me: Students share personal emotional responses to the art or music and how it resonates with them.

We: The class considers the artwork or music’s cultural or historical importance and its impact or reflection on broader societal themes.

As I bring this five-part series on thinking routines to a close, I want to emphasize that these routines aren’t just pedagogical techniques; they are foundational building blocks that foster genuine curiosity, encourage introspection, and deepen understanding. As educators, our mission extends beyond teaching a curriculum – it’s about shaping self-aware, critical thinkers who can navigate an increasingly complex world. By integrating these thinking routines into our classrooms, we provide students with the opportunity to delve deeper into the subject matter and gain insights into their developing identities as learners. These thinking routines encourage students to question, connect, and reflect with the goal of helping them become more knowledgeable, confident, and self-aware.

4 Responses

One thing I love about your work is you have the capacity and ability to take what’s in my brain and organize it. Thank you for this resource.

You’re so welcome, Kelly! I am thrilled these resources are helpful 😊

Take care.

Catlin

Thank you for all these thinking routines, they have been so helpful in my classes. Wonderful and useful resources.

Regards,

Cynthia

Yay! I’m thrilled they’ve been useful, Cynthia! I love them and wanted to make it easier for teachers to use them with students.

Take care.

Catlin