Give Students Writing Feedback That Works

How Our English Department Worked Together to Create a Coherent System

By Laurie Miller Hornik

With appreciation and gratitude for the members of the 2017-18 Middle School English Department of the Ethical Culture Fieldston School: Brad Fraver, Sharan Gill, Mollie Glasser, Casey O’Leary, Lauren Porosoff, and Debora St-Claire

With appreciation and gratitude for the members of the 2017-18 Middle School English Department of the Ethical Culture Fieldston School: Brad Fraver, Sharan Gill, Mollie Glasser, Casey O’Leary, Lauren Porosoff, and Debora St-Claire

The problem: how to respond to and assess our students’ major writing assignments. Every few weeks I collected another set of finished essays or vignette collections or some other major assignment in English. I had already given students comments as they were working, but now they had completed something significant. As their writing teacher, it was time for me to respond to and assess their finished work.

Over the years, my department colleagues and I tried many different approaches to these final comments. Some of us collected portfolios of work, an onerous practice that was hard to keep up over time. Some put letter grades on individual papers, but revealed the grades only after students had read the teachers’ comments.

Some used rubrics, assigning points for individual areas like “organization” and “voice.” Some reacted more personally to the ideas in the pieces. Some tried to focus on specific writing advice.

These multiple approaches created a disjointed experience for our students and didn’t communicate a clear message about what the department valued in writing. We just weren’t sure what would be best, so we kept trying different methods in the hopes of something working.

Yet we all agreed that our students would benefit from a thoughtful, coherent approach – and the best way to figure out that approach would be together.

Teacher Collaboration: Growing in a Common Direction

We began using the Collaborative Assessment Conference Protocol from the Center for Leadership and Educational Equity to look together at student writing and ask two questions: “What does this writer know how to do?” and “What is this writer working on?”

As we listened to how we each thought about student writing, we learned from each other, discovered our shared values, and began to grow in a common direction.

Our school supported our work by giving us a half day to meet for what we called a “Summit,” aimed at developing a new department-wide approach to giving feedback on major writing assignments. To set the tone for our collaborative work, we began with this warm up: What new thing are you doing this year that was inspired by a colleague?

We described learning from Casey about the value of thanking students for their work as part of teacher feedback. We thanked Debora for her metaphor of discussion: a set of connected comments that are “a string of pearls.”

We expressed our gratitude to Brad for teaching us the power of valuing not knowing and uncertainty and helping normalize students’ questions and even confusions. We learned about Sharan’s Cognitive Warm Ups – beginning class with creative free writes that got everyone writing, sharing, and listening right away.

The rest of our Summit focused specifically on our current practices. How we respond to and assess student writing? What does our feedback look like now? How has it evolved over time? What do we ask students to do with our feedback? And what do they actually do with it?

We examined Lauren and Mollie’s sixth grade single-point rubrics and used the prompts “I notice…” “I wonder…” and “I heard…” to help us analyze what these rubrics communicated to students about what good writing is and how writers grow. We considered the specific language we used on rubrics and in comments and the ways students heard and interacted with our feedback.

Three Types of Feedback: Reader, Writing Coach, and Evaluator

We came to understand together that the writing teacher plays three distinct roles, and our feedback needed to reflect all three, one at a time:

Teachers are readers, responding authentically to a text.

Teachers are readers, responding authentically to a text.- Teachers are writing coaches, giving student writers specific advice about what to keep on doing and what to work on doing in future pieces.

- Teachers are evaluators, telling students how well their writing aligns with stated criteria and benchmarks.

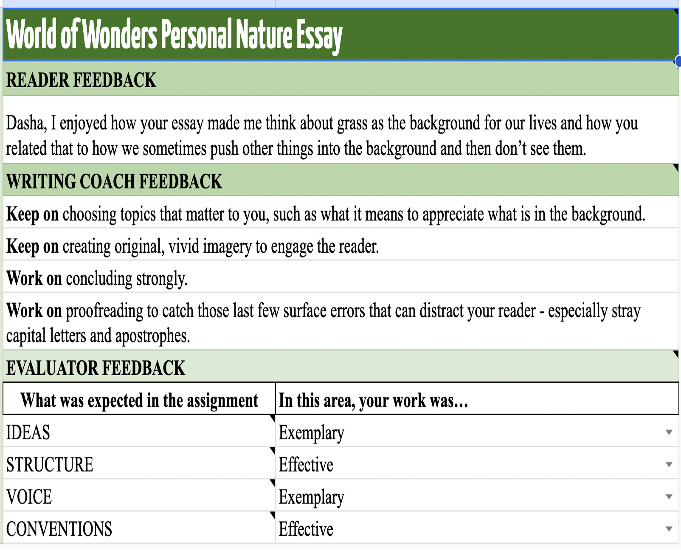

READER FEEDBACK

What Is Reader Feedback?

As a reader, the teacher reacts personally to the piece of student writing with curiosity and interest, just as a reader would react to any other text. We felt it was important to honor student writing by interacting with it as an interested reader first.

What Does Reader Feedback Look Like?

Reader feedback is a short paragraph – perhaps just a sentence or two – in which the teacher reacts authentically to something they liked or found interesting in the piece. Reader Feedback might include language like this:

- Your piece made me wonder…

- I was pulled in by…

- One of my favorite parts was…

- I enjoyed…

- When I read ___, it reminded me of…

- I was surprised to learn that…

WRITING COACH FEEDBACK

What is Writing Coach Feedback?

As a writing coach, the teacher recognizes what the writer is doing well and suggests next steps for their growth as a writer.

What Does Writing Coach Feedback Look Like?

One clear way to give writing coach feedback is to list specific Keep ons and Work ons. I usually aim for two of each. Keep ons and Work ons usually connect directly to the assignment rubric. Here are some examples of each:

- Keep on choosing topics that matter to you and developing them deeply.

- Keep on using strong imagery, like [include example from student writing].

- Work on organizing your ideas into paragraphs to help your reader follow them.

- Work on proofreading carefully, especially for missing punctuation.

EVALUATOR FEEDBACK

What Is Evaluator Feedback?

As an evaluator, the teacher identifies areas that do and do not meet expectations found in the rubric. Initially, my department had agreed on these three specific names for the levels of proficiency:

- Effective for the broad, middle level of work that meets expectations

- Exemplary for the top level – for work that is strong enough to be an “exemplar”

- Rudimentary for the bottom level – for work that does not meet expectations. We liked Rudimentary because it was a term that was fairly unfamiliar to students so would not sound derogatory or euphemistic. Over the next couple of years, we found it more helpful to call this level “Not Yet Effective” or “Developing.”

What Does Evaluator Feedback Look Like?

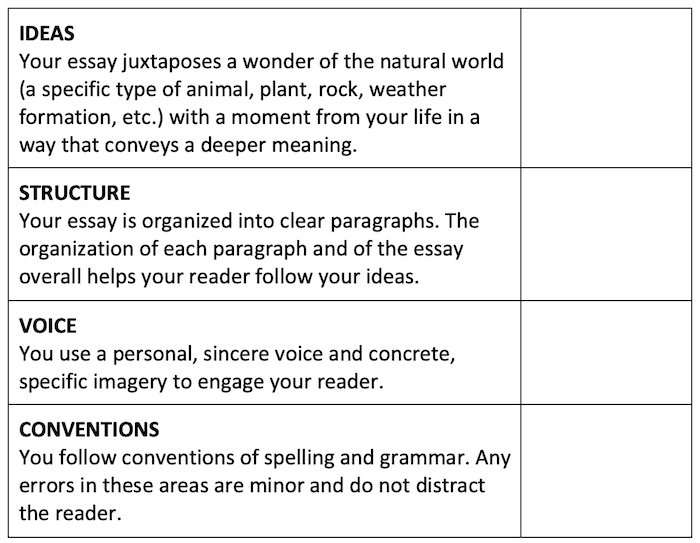

For evaluator feedback, we find it most useful to use a single-point rubric, which describes the “effective” level for each skill area rather than giving points or letter grades. Here is an example of a rubric I use for a seventh grade assignment in which students write their own personal nature essays based on essays we’ve read together by Aimee Nezhukumatathil in her book World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whalesharks, and Other Astonishments.

For each row, I indicate if the work is Exemplary, Effective, or Not Yet Effective.

Five Years Later

Our feedback system continues to be a success. Here are some tips we have found to be helpful over time:

- Create a cumulative Feedback File for each of your students to which you add the feedback you’ve given on each major assignment. This makes it easy for them to compare their feedback from one assignment to the next. You can even pass student Feedback Files to next year’s teachers.

- Keep the categories on the rubric (such as Ideas, Structure, Voice, Conventions) as similar as possible from assignment to assignment. This helps students see that the skills they are learning are transferable from one piece to the next, and it helps them apply the feedback to future assignments.

- Write up a description of your feedback system for parents and guardians. Share it with them at the beginning of each year and throughout the year as you give students feedback on their major writing assignments.

- Have students read and respond to their feedback after each major writing assignment. You can do this by asking students to choose one Keep on and one Work on to respond to, explaining in their own words what your “coaching” is in this area and giving an example from their work.

- Before each new major assignment, ask students to look back at their feedback on prior assignments and choose one or two Keep ons or Work ons that they think will be especially relevant to consider as they are writing their next piece.

- Finally, keep your feedback fairly short. If it’s too long, students might get overwhelmed or not read it. Here is an example of the full feedback I gave to one student on their essay (with the name and details changed):

Laurie Miller Hornik is a K-8 educator with over 30 years of experience. Currently, she teaches seventh grade English at an independent school in NYC. Laurie is the author of two middle-grade humorous novels, The Secrets of Ms. Snickle’s Class (Clarion, 2001) and Zoo School (Clarion, 2004). She writes a weekly Substack of humorous essays called Sometimes Silly, Sometimes Ridiculous and creates mixed media collages, which she shows and sells locally and on Etsy.

I liked your process and result. Excellent writing feedback system!