Sometimes the hardest part is just getting started. That probably holds true for a lot of people. But for some, like myself, it boils down to more than garden variety procrastination. It’s a research-backed phenomenon—and with a little work, it can be overcome.

I am a journalist, and sometimes (like with this story you’re reading), when I’ve wrapped up all my interviews, finished all my reporting and am ready to start writing, I just can’t seem to do it. I find myself cleaning up my email inbox or reading an article I’ve had open for a week—anything to avoid the blank page and blinking cursor where my draft should be. For a student like Andrew Leonard, a senior at East Wake Academy in Zebulon, N.C. in the thick of filling out college applications, that might mean putting off writing an admissions essay or sending in a transcript.

I am, unfortunately, quite familiar with this sensation. But until recently, I didn’t know that what I struggle with has a name: task initiation.

I first learned about it from Students LEAD (Learn, Explore, Advocate Differently), an online course developed by the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, with input from middle and high school students, to help learners understand and verbalize their individual strengths, preferences and needs when it comes to learning and working.

For some students, the course might validate what they already know about themselves, says Mary Ann Wolf, director of digital learning programs at the Friday Institute, an education research center housed on North Carolina State University’s campus. For others, it can be enlightening.

In either case, “we’re helping them learn how to articulate what they need to be successful,” Wolf tells EdSurge.

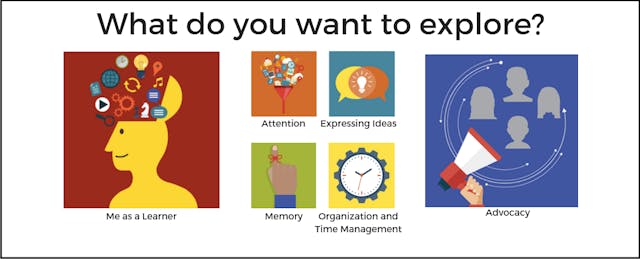

The course is free, interactive and self-paced, so you could shoulder through it in one sitting, like I did, or space it out over time. It takes approximately four hours to complete all six “zones” in the course, including those that explore attention, idea expression, memory, organization and time management.

As students move through the course responding to questions, polls and quizzes, the system aggregates their responses and generates an “action plan.” The plan highlights student strengths and challenge areas, and recommends goals, tips and tools for the student.

Ultimately, the course seeks to help students better understand and advocate for themselves as learners—now, and in the future, says Lauren Acree, the policy and personalized learning lead at the Friday Institute.

“I was a teacher, and one of the things I spent a lot of time doing was figuring out what made my students tick,” Acree explains, adding that if her students had already taken the course and entered her classroom ready to discuss their strengths and needs, it might have eliminated a major barrier. “Having the language to talk about these things and being able to name them is really empowering.”

Andrew Leonard, the senior at East Wake Academy who is working on college applications, participated in the pilot course last fall. He and about 150 other middle and high school students not only took the course but provided feedback about their learning experience. Based on the students’ suggestions, the Friday Institute altered the layout, navigation and some of the activities on the Students LEAD course, Acree says.

Leonard says that while he zipped through the modules and finished the course in just two days, what he learned during that time has stayed with him.

He says his action plan mostly confirmed what he already knew about himself: He learns best when he is with other people, mainly through group discussion and team-based projects. As for areas where he can improve, “I’m a procrastinator, and I don’t have the best memory,” he tells EdSurge.

But seeing those ideas materialize in the online course made him think about them differently. “It started to click that I really needed to be more organized,” he reflects.

The course recommends tools that can help students work toward their goals, so Leonard began incorporating some of them into his routine. He mostly uses apps on his phone, such as a digital planner and Apple’s “Reminders” app.

Leonard gets three or four reminders on his phone every night. He says that’s been especially helpful in his English class, where it’s not unusual to have overlapping essay assignments.

“[The apps] help me manage when I need to get things done and when I have free time,” he notes, even if it means “not relaxing when I want to relax.”

Lately, Leonard has been thinking a lot about next year, when he expects to be starting community college. He says he catches himself stalling on the admissions applications, but that with little nudges—even from his phone—he’s been able to stay on task.

Leonard is one of more than 600 students who have taken the course either during the pilot or since it was released in January.

Not for Kids Only: Reaching Educators and Families

A complementary course for educators, released in 2014, has been taken nearly 10,000 times. The educator course offers a primer on learning differences, with a special emphasis on executive function, working memory and student motivation. It was created with beginner educators in mind—specifically those in their first three years in the classroom, Wolf says—but teachers of all levels can and have taken it.

Two veteran teachers from East Wake Academy, Leigh Ann Lane and Liz Hall, recently took the educator course, and while they say most of the material in it reinforced concepts and constructs they were already well-versed in, they believe it would be a great fit for educators just starting out.

Lane and Hall, who co-teach a remedial writing class, said that over the past three months, they have also been guiding their students through the Students LEAD course at the recommendation of their superintendent.

“Some students were all about it,” Lane says. “It was validating for a lot of them, and gave them more tools for how to dig into their learning styles.”

In retrospect, Hall says they probably would have paced the course differently. In August and September, students spent an hour every Friday working through a new module in the course. As a result, it took students almost a month to complete the course and receive their action plans—far too long if you want to keep students interested and invested, Hall says.

“If we were to redo this next year, it would be more condensed,” she says, adding that they may try to fit the entire course into one week. “It lost the effect of what I think it could be.”

To complete the trifecta, the Friday Institute released a parent guide, “Letting Students LEAD,” in November 2018 to supplement the student course.

“A lot of times we hear the parents asking, ‘How do I help my child?’” Wolf says. This guide was designed with the hope that students will share their action plans—which can be downloaded, printed or accessed with a URL—with their parents and mentors, who will then be able to better understand and support them.