Gail Schlachter was a legendary librarian who built one of the earliest databases of financial aid opportunities.

Many people loved her. Many more loved her work. It began in the late 1970s, when Schlachter published a book of college scholarships for women. Then one for people of color. Then one for people with disabilities.

Schlachter transformed her research into a company, which became a life, which became a legacy. Students hungry for higher education even when few colleges cared much about them—they could go to a library, use Schlachter’s books and find money to fund their academic ambitions.

In the past four decades, college has only grown more expensive. Today’s students need scholarships more than ever. But the way they search for those opportunities has changed.

“The idea of somebody going to the library, and getting a book from a reference librarian, and writing down on paper the names of all the scholarships you might be interested in—that’s out,” says R. David Weber, Schlachter’s longtime collaborator and friend.

By 2015, the 72-year-old librarian knew she needed to make her scholarship data searchable online. She was on the verge of doing so when, suddenly, she died.

She left behind grateful friends and readers—and a meticulous database. The kind so well curated, catalogued and cross-referenced that it makes tech investors and entrepreneurs itchy with ideas.

What happened next reveals how the internet has changed the roles librarians play and the ways people find and think about information. It’s a story about what happens when that information shifts from being a public good to a private product, and about the hidden costs of data that looks free.

“The ending,” Schlachter’s son says, “is a little bit tragic.”

But only if it really is the ending.

(Courtesy of Sandy Hirsh)

The Librarian

The words people use to describe Schlachter are mystical. They say she was pixie-like. She was a whirlwind. She was radiant.

“Just bright and shining—this smile that would light up a stadium,” says Courtney Young, the university librarian at Colgate University.

And Schlachter also was savvy. In 1978, she published “The Directory of Financial Aids for Women.” In 1979, for the first time ever, women outnumbered men at U.S. colleges.

Schlachter came to the publishing industry through her research as an academic. She was the first person to earn a doctorate in library science from the University of Minnesota. That same year, 1971, she divorced her husband and moved with her two small children to Southern California, where she held librarian and professor positions at several universities. To help other doctoral students select thesis topics, she wrote an annotated bibliography of library science dissertations. When her publisher said a second edition would be too large to produce and asked her to narrow the project’s scope, she decided she was done with what she called the “intellectual compromises” of the traditional publishing process.

So Schlachter started Reference Service Press. It was a family endeavor, supported with $10,000 borrowed from her parents. Schlachter’s mom wrote invoices by hand. Her kids delivered books to the post office in red wagons.

“My brother and I were the fulfillment department,” says Sandy Hirsh, Schlachter’s daughter and associate dean for academics at the San José State University College of Professional and Global Education. “That’s what we would do at night after school. We would pack up books, fold up the flat pack boxes, putting the books in, using the tape to seal up the books, putting the labels on, putting the stamps on, putting the invoices in.”

(Courtesy of Sandy Hirsh)

At first, the press was a part-time project Schlachter tended on top of her university job, and, later, her role as an executive at ABC-Clio Press. But in 1985, she turned her full attention to running her company.

“Gail was an innovator,” Weber says, the kind of person he cited as an example in the economics classes he taught at Los Angeles Community College District. “I would talk about the role of a capitalist, an innovator, in an economic system. I said, ‘I know a person like that!’”

When a publishing periodical asked Schlachter to share business advice for other librarians, she offered this: “Identify a need, use your library skills to fill it, and learn how to sell it.”

The need Schlachter identified was scholarships. She was worried about reports that men received disproportionately more financial aid than women. Maybe there was an “information void” about the awards and grants that were available exclusively for women. Maybe she could tip the scales by tracking those opportunities down and sharing them.

“There was a radical shift in the population of students going to college, and all these great support programs for them, but no one place for the beneficiaries to learn about it,” says Eric Goldman, Schlachter’s son and a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law. “She was really motivated by this feminist concern. How can we get more women into college? Get them better treatment?”

The great interest libraries showed in buying “The Directory of Financial Aids for Women” signaled that Reference Service Press had found its niche.

The next book in Schlachter’s series was a “Directory of Financial Aids for Minorities,” later divided into separate volumes for African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. A book for veterans, military members and their families came in the late 1980s, as did one for people with disabilities. Then a guide for finding money to study abroad, and one for winning merit aid.

The books, often bound between white covers, became more specific, their titles sounding increasingly like phrases a student today might plug into a Google search: “Money for Graduate Students in the Health Sciences”; “Money for Christian College Students”; “How to Pay for Your Degree in Nursing.”

All of this was powered by the database of scholarships Schlachter created—which has grown to nearly 30,000 entries—each item intricately tagged to indicate which kinds of students ought to apply for which opportunities. As reader feedback relayed, this personalized approach to seeking financial aid worked.

“Coming from a low income background, with a single mother and three sisters, I did not think that I would ever have a chance to get a good university education,” wrote one former reader. “However, these books in the local library helped my sisters and I apply to and graduate from well ranked universities. I was even able to dream of law school because of my low undergraduate debt!”

Schlachter’s publishing company flourished. Her books earned awards. And all the while, she sustained her connections to the library community. She held officer roles in state and national organizations, serving as president of the American Library Association’s Reference and User Services Association and editor-in-chief of its journal. She was active in Reforma, an association that advocates for offering Latino and Spanish-speaking communities more library services and materials.

This kind of work, plus Schlachter’s “incredibly encouraging” welcome of newcomers to it, revealed her commitment to including others, Young says.

“Some people probably frame it and say Gail was ‘colorblind.’ That’s not it. She saw people for who they are. She had great interest in the potential in people,” Young says. “She was very interested in things that maybe would be perceived as radical from the outside but were sort of who she was on the inside.”

When Young ran for president of the American Library Association for 2014 and 2015, she asked Schlachter to serve as her campaign treasurer. Schlachter agreed, and later contributed her own money to the effort, so that Young wouldn’t worry about expenses.

Young won the race. The next year, Schlachter herself was elected to the association’s executive board.

(By Peter Hepburn, courtesy of Courtney Young)

“This was one of those crowning achievements for her,” Young says. “Serving together was a joy.”

At an ALA board meeting in April 2015, the friends posed for a photo wearing similar black-and-white skirts.

It was the last time they saw each other. A few days later, Schlachter checked into the hospital.

The Caretaker

A database is a living organism. The caretaker of this one is named Dave.

Each day, Dave wakes up, opens his computer and searches the internet for information about scholarships. He carries his 10-year-old laptop wherever he goes. He took it with him during a recent hospital stay, using the facility’s Wi-Fi to browse financial-aid websites from bed.

He doesn’t get paid for this work. Still, he keeps “whacking away,” as he describes it, aiming to update the database with new information for about a thousand scholarships each month.

“It’s so much a part of my life,” he says. “I like to joke to my friends, ‘If I wasn’t doing this, what would I do? Be hanging out in pool halls and bars?’”

This Dave is David Weber, and he first met Schlachter in graduate school in the Midwest. They lost touch after earning their degrees—history for him, library science for her—but reconnected later when they both wound up working in Southern California.

“She was my best friend, and I was hers,” Weber says.

Their kids had joint birthday parties. Each shared tidbits the other might appreciate, like when Schlachter tipped Weber off that an airline had a pass for unlimited plane rides. And when Weber was “kind of in a mess” after getting divorced, Schlachter pulled him into Reference Service Press, hiring him and assigning him to write the book on scholarships for veterans.

“They clicked. They were so in sync with each other as friends,” says Goldman, Schlachter’s son. “It lasted for decades, one of those great relationships that can develop between people.”

When Weber finds new information about a scholarship, he enters it into his database software. He still does some of the work in Microsoft Word. The main database file is 48.4 megabytes—almost too big for Word—so it gets sluggish.

“You don’t want to come around me on some days,” Weber says. “I use bad words. I swear in Spanish.”

Still, it’s easier than it used to be. The work Weber does online today, he and Schlachter used to do by hand. They sent letters in the mail to scholarship sponsors, asking them to write back with the latest information about the aid they offered. For Schlachter’s early books, she sliced typewritten pages into slips of paper and arranged them to be photographed, then printed.

“It was literally a cut-and-paste job,” Weber recalls.

The process evolved as technology improved. The database moved from paper to floppy disks to computer tapes to word processing programs.

Schlachter stretched beyond books to experiment with digital data delivery. By the mid-1990s, students could find the company’s research on CD-ROMs, or through America Online. Reference Service Press got its email address: findaid@aol.com. And the company signed licensing deals with organizations that wanted to make data available to their members. Customers included the Military Officers Association of America and the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

But Schlachter wanted to do more to make her data searchable online. She sought help from Eureka, a California nonprofit that offers digital job counseling services, whose tagline is “A Goldmine of Career Information.”

The librarian was not shy about her standards.

“She was very, very concerned about her data and how it would be used,” says M. Sumyyah Bilal, executive director of Eureka.

Schlachter visited the Eureka office all the time, Bilal says. The staff adored her. It tickled them to overhear the librarian instructing Bilal’s son about how to fix the website. He would later tease Bilal: “Why don’t you talk like Gail?”

“He just loved the way she would talk real sweet but never bend,” Bilal says. “She had a way of presenting to you some of the worst criticisms in the world in such an eloquent way that you felt good she had criticized you.”

Around the time of the Eureka collaboration, Reference Service Press book sales started to drop, Weber says. By 2015, the company’s prognosis was clear.

“Libraries that had subscribed to every book Reference Service Press published—major city libraries, they’d buy 10 copies of the women’s book—they were canceling their orders,” Weber says. “Libraries don’t use reference books anymore.”

They don’t even use the term “reference” anymore, says Steven Bell, associate university librarian at Temple University Libraries and former columnist for Library Journal. When his institution designed a new library, it scrapped the browsable reference section entirely, relegating the dwindling collection of big, non-circulating books to its Automated Storage and Retrieval System. Instead of print books, he and his colleagues now help students and faculty use aggregated digital databases like Credo Reference and Gale Virtual Reference Library.

“Those tools are much easier to search, you get the exact information you need,” Bell says. “Being able to subject search hundreds of encyclopedias at one time—from my perspective as a researcher and someone who teaches students how to do research, I feel they are much more robust and powerful tools.”

Meanwhile, Schlachter was waiting for a diagnosis of her own. She delayed getting a recommended medical test until after the ALA executive board meeting, and then went to the hospital for the routine procedure.

“She started to bleed, and she died,” Weber says. “How can you go to a hospital and die? That’s what happened. It was a shock.”

Schlachter had brought with her notes for a new book of scholarships for LGBT students, Weber says: “She literally died working on what would have been the latest addition to the RSP list of titles.”

The press was orphaned. So Weber adopted it. When he took the train, or went to the beach, or visited his second home in Mexico, the database was always within his reach.

Weber could carry on his friend’s research, but he couldn’t sustain the entire business.

That’s when an angel investor appeared.

Right: Gail Schlachter visiting a Reference Service Press book at a library or bookstore.

(Courtesy of Sandy Hirsh)

The Startup

For all the information that printed books give to readers, they don’t take any information from them in return.

That asymmetry is rare in internet publishing. Many websites ask users to share personal data. Many more simply take it without asking.

Giving information away at no cost is the librarian’s way. Drew Magliozzi, an entrepreneur in Boston, wonders if it can be his way, too.

He describes his vision for an open-access digital database of scholarships. It would be rigorously maintained. It would be free to use. And it would not collect students’ personal data—or at least wouldn’t sell it elsewhere.

“What I pitched to you is not a business in the slightest, which is a problem—which is why we haven’t done it,” Magliozzi says.

His dad and uncle are Click and Clack, the brothers who hosted the long-running NPR show “Car Talk.” And he’s the co-founder of AdmitHub, a company that develops chatbots for colleges. AdmitHub happens to possess a scholarship database purchased at the suggestion of one of the company’s early investors, Walter Winshall.

Before Winshall was a successful investor in technology startups, or co-founder of library technology companies SilverPlatter and Computer Library Services, or the subject of a 1967 TIME Magazine profile for enrolling simultaneously in law school at Harvard and business school at MIT, he went to high school in Detroit with a girl who grew up to be a librarian.

“Gail was a beloved friend of his,” Magliozzi says. “I’ve met at least a dozen people who say Gail was their best friend.”

Winshall and Schlachter were business partners first. In the late 1980s, when the librarian was dissatisfied with the services of one company that turned reference resources into digital databases, she tried working with Winshall’s company instead, and was impressed. As their friendship grew, Winshall accepted her offer to visit the press in California, where she worked with her dog.

“The phone would ring. She would take the call. She would say, ‘I’ll put you through,’” Winshall says. “She would go over to the desk that dealt with the sales calls—a different desk. She would transfer the call to the desk and take the call sitting at a new desk. It was fun, it was remarkable, appearing to be a substantially larger business than it was.”

After Schlachter died, Winshall tried to help her family find a new home for Reference Service Press. They wanted it to survive. They didn’t want to run it themselves.

The press was too small to interest large companies. So Winshall pitched it to Magliozzi, thinking AdmitHub might find a use for it.

Magliozzi was intrigued.

“On its surface, it looked like a book publishing company. It took a relatively sophisticated eye to see what it could be beyond simply what it was,” he says. “Simply a catalogue of scholarships was not interesting to me. The astounding thing was with the codebook for the data. It’s a catalogue of scholarships, but tagged, curated, as only someone with a library science degree would ever dream of.”

Printed out, the codebook is hundreds of pages long. It’s stuffed with the details Schlachter carefully collected about which students should apply for which scholarships. There are codes for everything, Magliozzi marvels, from students whose ancestors fought in the Civil War to students who are left-handed.

Perhaps, Magliozzi thought, such a thorough database could power a scholarship chatbot.

AdmitHub has cash now; in January 2020, it raised $7.5 million from big-name companies including Google and Salesforce. But at the time, the startup didn’t have much money in the bank. So it acquired Reference Service Press for debt.

Weber, the database caretaker, was part of the package. In exchange for his services, he got equity in AdmitHub.

“David really is the thing keeping it alive,” Magliozzi says of the database. “Without him, the thing would wither.”

Weber and AdmitHub continued to update and reprint books about scholarships. Within 12 months, the startup recouped its investment in the press, thanks to licensing fees from clients.

Meanwhile, AdmitHub built a prototype of a scholarship chatbot. The tool inquires about your age and gender, then moves on to questions about where you live, how much schooling you’ve completed and what you’d like to study. At the end of the conversation, the chatbot offers grant matches. Typically, some are for $500, others $10,000.

The product is good, Magliozzi says, but it needs a lot more work to be excellent—a resource that draws on behavioral science and artificial intelligence to be not only useful for students, but also enticing.

Either way, though, it’s no longer work that makes sense for AdmitHub, he says. Originally, the company set out to serve students directly. Then its business model changed. Now, most of its clients are universities. And it’s not clear where a scholarship chatbot—or the Reference Service Press database—fits in.

“In a startup with scarce resources, you only have time for your top priorities. First things first, second things never,” Magliozzi says. “It remains something that, opportunistically, I’m still interested in. But I’m basically trying to find the right partner who would do something with it.”

Competitors might take notice. More than 30 websites offer digital scholarship search tools, according to the National Scholarship Providers Association. Most of them are free for students—services that charge money are more likely to be scams, the association reports. Many sites collect user information, which they sell to third parties sniffing for new business leads or use to entice advertisers.

Maintaining the accuracy of these search tools is a challenge.

“Virtually every scholarship has some data that changes every year—like application deadlines, for example. But scholarship availability, amounts, eligibility criteria and other important aspects frequently change as well,” said Jackie Bright, executive director of the National Scholarship Providers Association, in an email interview. “So—staying on top of this amount of changing data, for the large number of scholarships in North America, is very difficult.”

Reference Service Press might have turned out like these sites. It was dipping its toe into the internet at the same time that Fastweb, another scholarship site, dove headfirst. Born in 1995, Fastweb used to employ a research team a half-dozen strong to find and vet financial aid opportunities, which it then matched to student users based on their personal characteristics. To stay current, it relied on tech tools that automatically searched scholarship websites for changes—work that Weber does manually. Fastweb is now owned by Monster.com.

Or the press may have morphed into Scholarship Universe, another service that matches students with personalized scholarship recommendations. The product, first developed at the University of Arizona, is now part of the portfolio of student financial services company CampusLogic, which sells subscriptions for it to colleges, which make it available to students for free.

Would these models please a librarian? That’s the question weighing on Magliozzi. He says he has a soft spot in his heart for free and open databases, and wonders whether a nonprofit would be willing to cover the costs of creating one out of Schlachter’s database. He envisions a “Wikipedia specifically for scholarships,” he says, one that empowers thousands of people to do the work Weber currently does alone.

“Where can this thing live digitally so that it’s out of one person’s hands and in the hands of everyone?” he muses.

Supporting a sophisticated scholarship search tool through philanthropy is possible—in theory, says Mark Kantrowitz, who helped to build the scholarship search system for Fastweb.

“It’s a very expensive enterprise to maintain a database,” explains Kantrowitz, publisher and vice president of research at SavingForCollege.com. “You gotta be selling it to someone. Either you’re selling to advertisers to advertise on the websites, or you’re associated with a nonprofit that has money from another source, and you’re using that to cover the cost.”

Weber knows AdmitHub doesn’t have clear plans for Reference Service Press. For the record, he’s not impressed by other digital financial aid databases he’s seen. He says they’re not accurate. That their data is bad. Or, that they make money by selling college students’ names, and he doesn’t like that.

“That’s the dilemma confronting AdmitHub today: How can you get this to work within the business we’re doing?” Weber says. “We’re not clear we have the answer.”

But a nonprofit for military families might.

(Courtesy of Sandy Hirsh)

The Beneficiaries

Brian Gawne is a foundation executive, a retired Naval flight officer and a father to three children born within five years. When the kids were in high school, Gawne sat them down and made his case.

“If I gave you $500 for an hour’s worth of work, would you do it?” he asked them. “What if I gave you $50 for an hour’s worth of work, would you do it?”

They were intrigued. Gawne continued.

“Here’s 10 small scholarship applications I want you to fill out,” he said. “It will probably take you an hour to write the application for each one. If you get only one, that’s $50 an hour. So, start writing.”

Gawne works for the Fisher House Foundation, a nonprofit that builds residences near military and veteran hospitals so that patients’ family members can stay nearby. The organization also offers scholarships to children of service members.

So Gawne knew that his Navy career might make merit aid available to help his own military kids pay for college. He tried the usual websites, but found their results too generic, figuring that every other parent in the country would also tell their children to apply for the obvious big corporate scholarships.

Then Gawne discovered a database hosted by the Military Officers Association of America. It had grants he wasn’t finding on scholarships.com. Grants tailored specifically to children of veterans, like his. Grants for kids whose parents were aviators. Grants from the Naval Officers Spouses Club of Washington D.C.

“We’ve narrowed the demographic so it’s not the general public,” Gawne says. “Chances are, there aren’t a lot of people aware of these.”

Eventually, the officers association dropped the database. Gawne thought Fisher House might fill the void. He called the organization up and asked where it got its data. The answer: Reference Service Press.

“That rang a bell,” Gawne said. “Back when my first was going to college, I remember going to the library and seeing their white book.”

Gawne tried to contact the press. He was redirected to AdmitHub. He did the math. For the price of 20 Fisher House Foundation scholarships a year, the nonprofit could fund a digital matching tool that connected more students with more money.

“We could try to do $2 million in scholarships ourselves, or for a small portion of that price, we could give access to tons of scholarships,” Gawne says. “Why reinvent the wheel when there are lots of wheels out there that people just don’t know about?”

He told AdmitHub, “I’d like a search engine.”

Since 2016, Fisher House has sponsored Scholarships for Service. It’s a tool that matches military families with relevant scholarships, powered by the 15 percent of Schlachter’s database dedicated to such opportunities.

It gives information freely.

“When we built our search engine, we didn’t have any ulterior motive. It was strictly to make a tool for students so they could find scholarships. We don’t collect their names or their addresses. There’s no intent to sell any of that stuff,” Gawne says. “If they give us their email, they can do their search, and it will print out a PDF, and it will email a PDF to them.”

Fisher House Foundation is pleased with the product, which attracted more than 21,000 visits between December 2019 and February 2020, more than 11,000 from new users.

The nonprofit renewed its data-licensing contract with AdmitHub last year. Magliozzi says that Scholarships for Service represents “the MVP”—or minimum viable product, as they say in the startup world—of what he would build out of Reference Service Press, if he found the right partner.

“I don’t want to make money off of it, I’d give it away,” he says. “All I want is a footnote that says we are involved. We are only one chapter of the story that is the database and Gail’s life.”

(Courtesy of Eric Goldman)

Gail Schlachter was a legendary librarian. She’s honored in the California Library Hall of Fame. Her papers are in the archives at two universities. Her publishing company gave more than $150,000 in scholarships to more than 50 library-school students, and her family gives research grants in her name. Her books are for sale on Amazon. They include her last new title: “How to Pay for Your Degree in Library & Information Science.”

The values Schlachter lived are the same ones librarians still need today.

“The focus on intellectual freedom, creating access to information with the fewest barriers possible, being someone who is active in the community, creating the library to be a welcoming place—those things have always been part of what we do,” Bell, of Temple University, says.

But technology has made the role more complex than it was in the past, he adds. Data used to be scarce. Now, it’s everywhere.

“The challenge is for the librarian: What’s the value you bring to helping people find information?” Bell says.

The challenge is for Reference Service Press: Who will pay for that value?

Magliozzi publishes updates of Schlachter’s books and ponders the future. Weber refreshes her database and remembers the past. At library conferences, librarians stop her daughter in the hallways.

“I still have people coming up to me telling me how much they miss her, what a difference she made in their lives, how much she mentored them, encouraged and believed in them,” Hirsh says. “These books are an extension of that, when you think about it.”

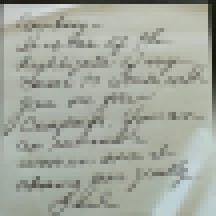

(Courtesy of Courtney Young)

Schlachter’s light flashes without warning. One day, while Young was preparing boxes for her move to a new librarian job in a new state, a familiar scrawl caught her eye, on a Post-it note Schlachter must have tucked into a piece of mail:

You are an incredible woman and I admire you greatly. Gail.

“I’m the one who should be writing those notes to her. I’m the one who should be telling her things like that,” Young says. “Sometimes we wait to do that.” ⚡