By: Gabby Hewitt & Drew Schantz on April 26th, 2021

Post-Pandemic Possibilities for School

About a year ago, we dealt with one of the largest supply shortages we've faced as a modern country. While toilet paper was certainly in high demand, it was actually active dry yeast that had people scrambling. New and aspiring bakers that found themselves with additional time at home were inspired to learn a new skill: how to make homemade bread amidst the backdrop of a global pandemic.

Perhaps you, too, found yourself shifting your attention to the stove. Without the ability to safely dine out at restaurants, many of us have rekindled their relationships with their kitchens, dusted off pots and pans, and gotten around to try out that piri piri chicken recipe. Alternatively, for those who haven’t been motivated to take the steps to becoming the next Iron Chef, scores of restaurants have made their offerings available online. And with a few taps or clicks, that piri piri chicken is at your doorstep without a single kitchen utensil or pot being dirtied.

Now, more than a year into the pandemic, we are nearing a time when the light at the end of the tunnel is just beginning to get brighter: it’s a time to take a step back and ask ourselves, what should that future look like when we emerge from the metaphorical tunnel? How might we apply what we have learned over the past 13 months to contribute to a more equitable, sustainable, and joyful world? Will we abandon what we’ve learned in the kitchen? Will we delete GrubHub from our phones? Probably not. The culinary possibilities of the future have been accelerated by the changes that have taken place this past year, and they’re here to stay. Generally speaking, we now have more freedom and flexibility with how we source our next meal.

Education is no less facing these same questions: What have we learned? What can we leave behind? And what should the future look like? Now is our opportunity to shape it.

THE MIRROR AND THE MAGNIFYING GLASS

When thinking about this unique opportunity we have to shape the future of education, it’s helpful to consider the simple coaching metaphor of using a mirror before a magnifying glass. When difficult or even catastrophic events happen, human nature primes us to dissect what went wrong (the magnifying glass) before looking at our own actions and reactions (the mirror). We propose that both lenses are important for reflecting on “The Pandemic Year,” and acknowledging that “back to normal” in education is not an option. Let’s face it — normal wasn’t that great, nor was it working for all students. Our system of schooling was not designed for students of color, marginalized, or underrepresented groups, such as, students with low socioeconomic mobility, or students with disabilities and learning differences. The good news is that because our education system was designed to yield the results that we currently see, it can be redesigned.

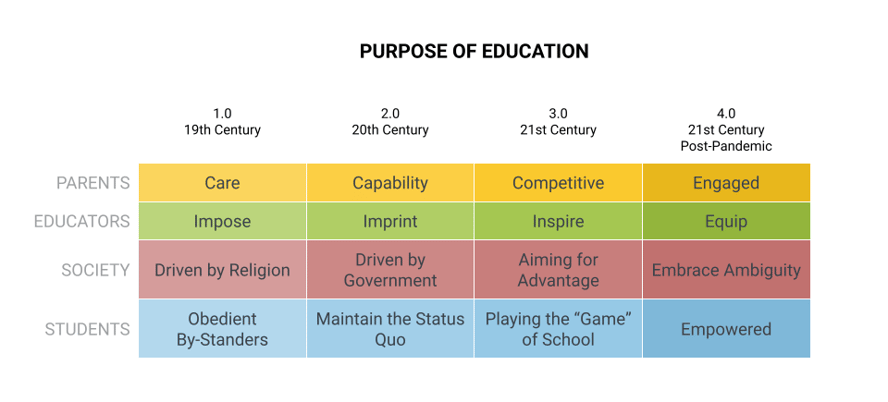

Speaker and author Matt Church has classified the evolution of education (we’re interpreting it as the evolution of schooling) into three primary phases, driven by three factors: parents, educators, and society:

-png-1.png?width=825&name=Post-Pandemic%20Possibilities%20Charts%20(2)-png-1.png)

While this breakdown could be perceived as accurate for students for whom the education system was designed, marginalized students, in many cases, are still experiencing Education 1.0 — a system in which students are expected to be compliant, participate in a process permeated by white supremacy, and focused on indoctrination rather than liberation.

Here’s a revised version:

To optimize our opportunity to move away from this system, educators should first use the mirror to reflect on what has worked in the past.

THE MIRROR: REFLECTING ON SUCCESSES

While it’s easy to analyze what’s been lost, we should first take stock of the tools, resources, and learnings we have acquired over an uncommon year to see what should become standard for us in the academic years to come.

While it’s easy to analyze what’s been lost, we should first take stock of the tools, resources, and learnings we have acquired over an uncommon year to see what should become standard for us in the academic years to come.

In the research world, 2020 would be called an “edge case” - a situation so extreme that it was beyond predictable parameters. It would be logical to think that what works in an edge case is not as useful for a base case or a typical year. But edge cases are powerful examples of how innovative thinking is not only good for extreme parameters - they are inclusive of many other situations. The ADA-compliant bathroom stall was designed for someone using mobility equipment, but ADA-compliant stall is also relevant for someone traveling with a service animal or a parent with a young child needing the changing station. The Nalgene water bottle was originally created to withstand high temperatures in science laboratories, but quickly showed promise as a lightweight and leak proof hiking accessory. Even Amazon’s Alexa that was designed as a hub for smart home devices, has a use case for the busy adult cooking that piri piri chicken hands free, or the child who wants to hear the latest Cocomelon song. Edge cases allow us to reflect on where success in one extreme situation might breed success in another.

2020 was definitely an education edge case. The country and world was hit with a global pandemic that not only stopped traditional routines as we knew it, but halted traditional in-person learning for a solid year. By using a mirror to reflect on successes from this edge case, we can more greatly apply learnings to what we predict will be a return to a more traditional school year in Fall 2021.

For example, a pre-pandemic parent-teacher conference schedule required parents and guardians to schedule individual time during the work day to drive to a campus and meet with a teacher for a scheduled time slot on a single day (or miss out on the opportunity to formally connect with a teacher altogether if their schedules did not allow). This practice limited the teacher to time slots on predetermined days, as well. School closures from the pandemic led to virtual parent-teacher conferences over Zoom and Google Meet and provided more flexibility for both teachers and families. This edge case demonstrated a new way to engage with parents and families. Imagine how we can bring this into our standard operating procedures of communication and create more flexible opportunities to connect beyond the pandemic closures. By using a mirror to reflect on our learnings and successes from this year (hint: think of your edge cases, first), we can shift school and district practices to make them even more responsive and agile for any future disruptions.

THE MAGNIFYING GLASS: ANALYZING FAILURES

Along with the surprising successes from the last year we can learn from a reflection practice, we should also use a magnifying glass to analyze perceived failures. The word failure itself can be very heavy - it frequently carries feelings of frustration, defeat, and a sense of loss in a year where losses are plentiful. However, responsive schools and districts have learned to equate failure with learning and insight. Famous author James Joyce compared mistakes and errors to “portals of discovery” in his most famous work Ulysses. Ray Dalio, CEO of the famous firm Bridgewater Associates requires an extreme form of feedback transparency that looks at failure in the same way a scientist looks at data. (Consequently, Mr. Dalio’s Twitter Bio lists his identity as a “professional mistake maker.”)

Along with the surprising successes from the last year we can learn from a reflection practice, we should also use a magnifying glass to analyze perceived failures. The word failure itself can be very heavy - it frequently carries feelings of frustration, defeat, and a sense of loss in a year where losses are plentiful. However, responsive schools and districts have learned to equate failure with learning and insight. Famous author James Joyce compared mistakes and errors to “portals of discovery” in his most famous work Ulysses. Ray Dalio, CEO of the famous firm Bridgewater Associates requires an extreme form of feedback transparency that looks at failure in the same way a scientist looks at data. (Consequently, Mr. Dalio’s Twitter Bio lists his identity as a “professional mistake maker.”)

Leaders should consider using a magnifying glass to analyze failure, not to assign blame or relive loss, but rather to consider what can be learned from and used as data when planning for a post-pandemic reality.

Many industries have embraced this concept already of analyzing failure as data. Athletes and coaches alike run tape after games to dissect where a different play could have been called. Businesses like Starbucks and Apple have analyzed failure at the brink of their financial loss and bankruptcy, respectively, to rethink products, services, and marketing strategies. Education should be the next industry to use this magnifying glass approach to analysis to learn from the perceived failures of the past year.

For example, your district may have tried a new team teaching strategy this year. One teacher may have been considered the lead teacher for “Roomers” - or students attending instruction in person, while another teacher may have been considered the lead teacher for “Zoomers” - or the students attending classes virtually over a video conferencing platform. Even if this strategy did not produce the desired results, you likely learned a powerful lesson on collaboration and instructional models. By using a magnifying glass to analyze your perceived failures, you have prime data for post-pandemic opportunities.

POST-PANDEMIC POSSIBILITY

Once you’ve reflected and analyzed your own experiences as a team, school, and district over the past year, your team can consider what lessons it will carry into the upcoming one.

As we collect similar learnings from district leaders, we plan to synthesize and share trends in a follow-up post to this blog. The second part of this series will focus on lessons from education leaders, support with decision-making for your post-pandemic year, and shifts for the future that can help us make shifts in our classrooms, teams, and maybe even the occasional kitchen.

About Gabby Hewitt & Drew Schantz

Gabby is an Associate Partner. Born and raised in New Orleans, she is an avid Louisiana sports fan and is raising two young fans. Drew is a Design Principal and is passionate about leveraging the power of entrepreneurial thinking to drive equitable and systemic change in education.