How Democratized STEM Can Close Opportunity Gaps

contributed by Catherine Stein

There’s little doubt that students with strong STEM skills will have greater opportunities. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics forecasts an 8% increase in STEM jobs over the next decade.

But according to the most recent NAEP scores, 40% of high school seniors are performing below the basic level in math and science. And when you really dig into the scores, it becomes painfully obvious that there are some huge disparities between some students and others. Asian and white students demonstrated proficiency at rates far greater than their Hispanic and Black peers. Students whose parents had graduated college were far more likely to demonstrate proficiency than those whose parents held only a high school diploma. Why is this alarming? Because it suggests STEM careers will largely only be opportunities for those with plenty already.

But that doesn’t have to be the case.

I came to teaching through Teach for America, and as such, the first district I worked in was very diverse and had a high poverty rate. I struggled to find resources and equipment. I wasn’t provided a curriculum, so I had to develop that on my own. What I was experiencing wasn’t unique. This lack of resources is so common that it’s just assumed and expected in rural schools, and in urban ones, for that matter. In one recent survey, 73% of rural science teachers and 78% of urban science teachers said they didn’t have adequate funding to do their jobs properly, compared with just 63% of suburban science teachers surveyed. Suburban teachers reported receiving 2.5 times as much funding for classroom supplies as urban teachers and 1.3 times as much as rural educators.

See also Drawing Ideas: The Benefits Of Mindmapping For Learning

It was clear that my students weren’t getting what they deserved, so I became very motivated to ensure they had all the same opportunities their neighbors were receiving at the local private school. I recognize that teachers cannot be responsible for all the inequity in our education system, but there are steps we can take as individual practitioners to open the doors for all students—not just the privileged—to access STEM:

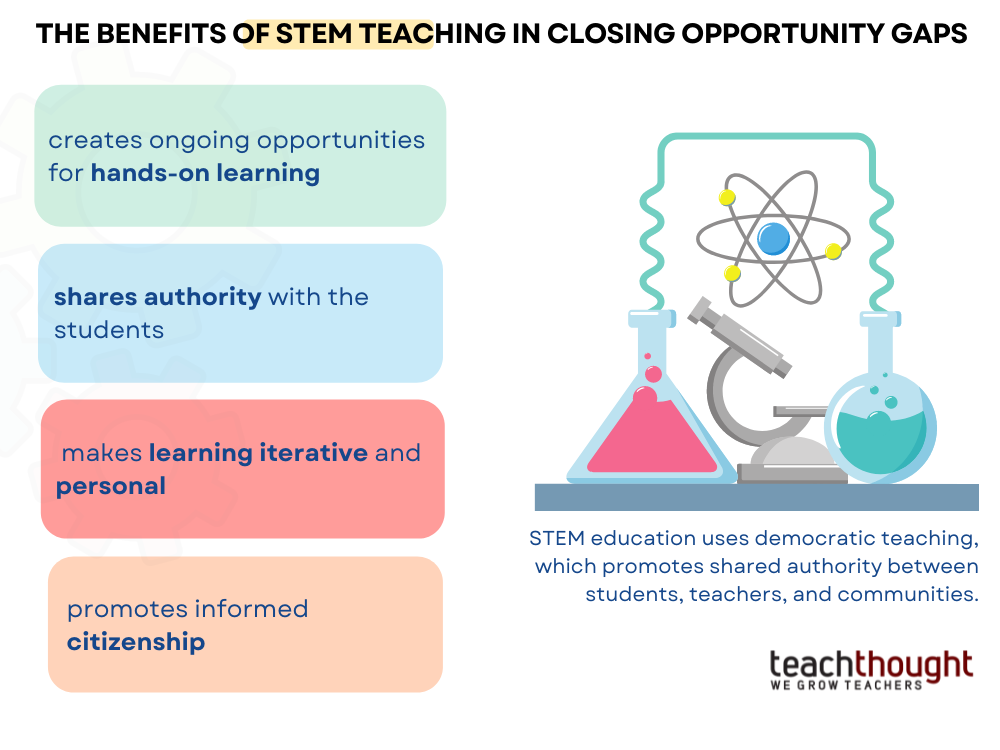

1. It can create ongoing opportunities for hands-on learning

These experiences are critically important for sparking interest in STEM, especially for students in under-resourced schools. Hands-on learning gives students the ability to see and understand what is happening in front of them; it allows them to explain critical science concepts and make sense of the world by drawing on their experiences and their own funds of knowledge.

My students love labs. When they see me wearing my lab goggles over my head and setting materials up in the morning, they all ask me eagerly what they’re going to do. And it opens up conversations with them about the habits and skills we build in order to become professional scientists. Whether we are examining our own cheek cells, dissecting frogs, or modeling global warming on a small scale, students have the opportunity to experience science firsthand and develop their own conclusions about the world around them.

2. It shares authority with the students

As a STEM Ed Innovator Fellow, I believe strongly in the power of democratic teaching, which centers on shared authority between students and teachers, prioritizing student voice, and empowering students to take action on issues that affect their lives as a result of STEM education.

Shared authority is not a new pedagogical approach, but I believe it is both under-taught and underutilized across the teaching profession, particularly amongst teachers who profess to take a “whole child” approach to education. In fact, there is research that suggests that a shared authority pedagogy aligns favorably with an approach to teaching that places high value on the fact that children express themselves and are active in their education.

And while I cannot say that each individual student would do better or worse if I didn’t share that authority with them, I can say that my students’ abilities to make claims, explain data, and read informational texts grows so much throughout the year that it often takes me by surprise; and they consistently credit that growth on being able to express agency in their learning.

3. It can make learning iterative and personal

In a different world, it would be obvious to all children, regardless of their race or gender, that they belong in STEM. But that isn’t the world our students live in. They can’t always see themselves reflected in STEM, so it is imperative that we as educators connect STEM to their personal lives if we want to make their learning meaningful. I center my lessons on challenges and problems that they are facing in their actual lives. And that’s powerful because traditionally, we haven’t asked these students to bring their lives into the classroom. In fact, we have expected that they check their lives at the classroom door.

4. It can promote informed citizenship

When I give my students permission to experience their learning personally, it increases their investment in the curriculum, and it also builds their capacity as responsible citizens in making informed choices for themselves, because they can understand the data and information that comes at them in the real world. Becoming agents of their own learning will take students much farther than a teacher telling them exactly what they need to do and why they need to do it.

With an explosion in STEM career opportunities, now is the time to expand the population of students who ‘belong’ in STEM—not just because we need more STEMists, but because greater representation in the field will allow us to tackle the unique challenges facing underrepresented communities. When we invite all students into our science and math classrooms in more meaningful ways, we give everyone a chance to change the world.

Catherine Stein teaches middle school science at Match Charter School, and is a STEM Ed Innovator Fellow. She can be reached at email [email protected].