Microsoft Exec. Challenges Publishers to Change, as Students’ Use of Technology Shifts

Philadelphia

Learning has been transformed globally by new ways of using technology outside classrooms—but schools and education systems mostly have remained stagnant in how they use digital applications for teaching and learning, Anthony Salcito, Microsoft’s vice president for worldwide education, told publishing executives gathered here Tuesday.

One of the reasons is that too much of the discussion is about what to do with the technology, not enough about strategies for changing how educators teach and how students learn in school, said Salcito, who was a keynote speaker for Content in Context 2016, the annual conference of the Association of American Publishers Pre-K-12 Learning Group.

“The challenge we all face in the industry is to lift the expectations” for students, school leaders and other education decision makers, he said.

“In many cases, their expectation, their ambition, is to automate or digitize, not transform. We need to shape what that means.”

In his role, Salcito meets with education leaders around the world, and when the pace of change comes up, he hears a common refrain.

“The senior officials are almost apologetic to me as an official for Microsoft,” he said, telling him that within the next five years some large percentage of their teachers will be retiring. Their excitement is for a new wave of teachers who are technologically savvy and enthusiastic, he said, but it’s teaching they should consider as much as technological skills. That’s how much technology is driving

“It’s great to have amazing digital books, tablets, devices, but in many cases technology comes into schools, and they [school officials] start asking, ‘How do we use it?’ ” he said.

In the meantime, students are creating, taking pictures and video, learning from their devices and sharing their knowledge and experiences outside of school all the time.

‘Your Students Are Learning Without You’

How educators respond to this simple statement—which Salcito at one point put on a projector screen behind him during his presentation— is “an easy way for a teacher or school leader to evaluate their own readiness for change,” he said.

When teachers around the world read it, “you can imagine, many of them don’t say ‘Hooray, Yippee!’ ” he said. “Unfortunately, this is a threat to teachers. That’s a problem.”

But when Salcito substitutes other verbs—”Your students are studying without you” or “Your students are reading without you”—teachers’ reactions are more receptive, and it shows the possibilities for change.

“The learning that’s been in the hands of educators has fundamentally blown up,” Salcito said. Students “can learn from the world of content all of you provide, from the world of experiences … and teachers who understand and embrace that, those teachers have transformed.”

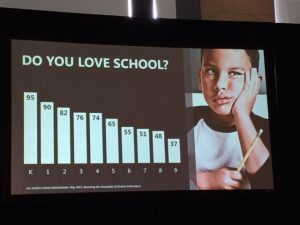

In another slide used for his presentation (pictured above, right), Salcito showed a measure of students’ declining enthusiasm for schools as they move through the K-12 system. Salcito said personalization and the “maker” movement in education are two forces can help change students’ attitudes, and re-engage them.

Salcito challenged the group to raise their expectations about what personalization means, so that “it’s deeply connected to who we are as individuals.”

Digital tools should “know” information like your name, age, reading level, accessibility needs, race, and gender—for the purposes of customizing lessons that are relevant to their backgrounds. The pictures in the digital resources should reflect the culture and perhaps even the religion of the reader, he said. “If my book knew I wanted to be an architect, my math problems could give me architectural examples,” he said.

Personalization also means knowing what a student has already learned, what books he or she has read, to add context to the information that is presented.

“We’re moving beyond ‘choose your own adventure,’ to a world where there is fundamentally no Page 2 in a learning resource,” he said.

Making a Case for ‘Making’

Schools and developers have the opportunity to capitalize on students’ love of creating things and sharing that experience with others, through the use of maker spaces and other kinds of maker education, Salcito argued.

“We’ve got to harness this through the work we do with technology,” he said.

In the United Kingdom, Microsoft is partnering with other organizations and schools in an initiative to provide micro:bit computers to every student in early in middle school. The device is a pocket-sized code-able computer with motion detection, a built-in compass and Bluetooth technology.

Microsoft is also promoting the #MakeWhatsNext campaign, to help girls understand the fact that there are women who have created life-changing inventions, and to give them the idea that they could follow in those female footsteps.

What Schools Everywhere Want

Salcito said school leaders across countries are facing the same sorts of pressures, and have similar interests in creating personalized, immersive experiences for students.

“Schools have less money, less resources and higher demand for performance,” he said. In some cases, the educational needs of countries are changing as their economies change. Saudi Arabia, for instance, has seen diminishing revenues from oil, and so its leaders want to “reboot” their school system, Salcito said.

Microsoft is preparing to launch its MinecraftEDU for schools this fall, Salcito said. The company acquired the popular game earlier this year. The question, he said, is “How do we power this amazing world of the sandbox to create new learning experiences?”

To underline his point that learning is not dependent on technology, Salcito said most of the world of Minecraft is happening outside of the game. Studies show that users spend less than half of their overall time with Minecraft is inside the game, Salcito said, as students access YouTube videos and collaborate on plans offline.

In an interview after the keynote, Salcito talked about how Philadelphia has shaped his thinking about what works—and what does not—in education. Microsoft launched its first showcase school, “The School of the Future,” in the city about 10 years ago. Today, there are 621 of Microsoft showcase schools around the world, he said.

The idea behind the $62 million facility that opened in 2006 was to use a computer-based curriculum delivered with the latest technology tools. But Salcito said visiting with parents who would send their children to the school, he learned that their biggest concern was not curriculum, or technology—it was safety.

The school, built in historic Fairmount Park has faced its challenges over the years, but Salcito said no graffiti is on its walls today, a sign that the school is an institution that the community is proud of.

“When we see great transformation happening in schools, it’s because of the people stuff,” he said. “It’s thinking about everything from student expectations to parent involvement to the thoughtful use of technology. It’s put in the right order.”

See also: