Research Guidance for Ed-Tech Industry Updated on Usage, Other Criteria for ESSA Evidence Levels

Research guidelines for ed-tech companies, produced in conjunction with an industry association, have been revised to provide more information about different levels of research, and to get faster answers about “what works” in the K-12 marketplace.

New recommendations on research relating to usage data, implementation issues, and findings for subgroups have been added to best practices to evaluate and increase the impact of ed-tech products from Empirical Education Inc. and the Education Technology Industry Network, (ETIN), a division of the Software and Information Industry Association (SIIA). The Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting EdTech Impact Research in U.S. K-12 Schools were originally released in July 2017.

“Most research ends up not really benefiting anybody,” said Mitch Weisburgh, president of ETIN and managing partner of Academic Business Advisors, LLC. “We’ve been caught up with the same type of research pharmaceutical companies use. That research doesn’t work for education. It’s too big, too expensive, and it takes too long.”

At the same time, companies that unilaterally declare that their products “work” aren’t giving a complete picture. “It’s not like any particular product works for all students all of the time. Part of the charge is to figure out what subgroup of students the product works best for, and how,” Weisburgh said.

A nimbler, more agile version of research is covered in the update to the original release of guidelines, he said. It still reflects 16 best practices for the design, implementation, and reporting of efficacy research for ed-tech developers, publishers and service providers of K-12 ed-tech products.

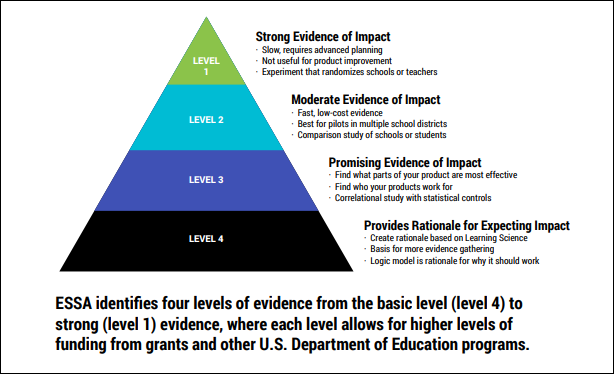

Using the tiers of evidence set forth in the Every Student Succeeds Act, the updated guidelines add more information for ed-tech providers that align with the Level 3 (showing promising evidence of impact) and Level 4 (providing a rationale for expecting impact.) [See above chart.] Weisburgh said the earlier version focused more on the bigger studies that take longer and are more costly.

The update reflects feedback that the authors received after releasing the original document, to clarify issues around providing research about what schools need to make decisions, said Denis Newman, CEO and founder of Empirical Education Inc., a Silicon Valley-based research and development company that was commissioned to produce the original guidelines and the update.

The current edition advocates for analysis of usage patterns in the data collected routinely by ed-tech applications. These patterns help to identify classrooms and schools with adequate implementation and lead to lower-cost, faster turn-around research, the researchers wrote. They also identified advantages of looking at subgroup analysis to better understand how and for whom the product works best, in an effort to answer common educator questions more directly.

So rather than investing hundreds of thousands of dollars in a single large-scale study that meets the strictest research standards with a randomized control study, companies should consider multiple small-scale studies, Newman said. This approach means companies can use the findings as needed to modify their products.

More information about the additions to the guidelines in three areas are explained below.

The importance of focusing on subgroup analysis to show schools what will work for their specific needs.

“Schools want to know what works for them, given their population and resources,” said Newman. “They need to know about which subgroups in a study got more or less benefit from a product, and that should be a focus of research.”

Although educators can use the What Works Clearinghouse from the Institute of Education Sciences to locate research findings in schools with similar demographics to theirs, they can’t search for the differential impact of a program on a certain subgroup of students, Newman pointed out. The subgroup impact is standard practice in research, but the clearinghouse only reports the overall average in its summary reviews, he said. School decisionmakers must consult the original research reports to get those findings.

“I often point out a big project we did for a regional lab in the Southeast,” he said. The study in Alabama found that a STEM program had a small overall effect on math. “But it didn’t work as well for the black kids as for the white kids,” he said, referring to the subgroup impact analysis. That information is included in the report, on page 299.

Besides looking at subgroups like race and sex, ed-tech companies will want to show a product’s usefulness to potential new customers. For that, the report said it’s important to be able to answer questions like, “Is the product more effective for high-achieving students or for students below grade level?” or “Did experienced teachers find it more useful than novice teachers?”

Analyzing usage data is key to allowing a research project or efficacy study to be done quickly and efficiently at low cost.

Monitoring cloud-based data about how products are used allows researchers to look at the patterns of implementation, to see where an ed-tech product is being utilized at a level that educators can expect an impact, said Newman. “ESSA allows a study that looks at the amount of usage as related to outcomes like test scores,” he said. Or, whether increased usage of a product in a classroom produces a higher attendance rate or a lower dropout rate, he said.

“Because we’ve moved from books that provide no data on their own, to software products that pull data automatically, you can do research based on data from that product,” said Weisburgh. However, it’s important to start with the end in mind, understanding what you need from the research to help educators make decisions.

Research is needed about the quality of the implementation of an ed-tech product to understand what makes it successful in schools.

It’s not enough to know that a certain product “gets implemented well under these conditions, but not those conditions,” said Newman, “if, under the best of conditions, it still doesn’t work.”

A product that might be fun to use, and that gets a lot of classroom time, could still lack the desired impact, according to Newman. “You still need to know the conditions under which it works,” he said.

The updated version of the guidelines emphasizes various considerations around issues with the quality of implementation.

The authors caution that the guidelines represent “a working hypothesis based on experience in the Investing in Innovation (i3) program, close review of the ESSA legislation and guidance, and conversations with other researchers.”

The document is designed to be updated as more developments occur, including any potential legislative movement on the Education Sciences Reform Act, which authorizes the Institute of Education Sciences and is more than a decade overdue for reauthorization.

Follow EdWeek Market Brief on Twitter @EdMarketBrief or connect with us on LinkedIn.

See also:

- New Guidance on Conducting Research Unveiled for Ed-Tech Companies

- How to Build a Research Base for Your K-12 Product

- Breaking Down the New Ed. Law’s Research Mandate for Vendors

- Peer-Reviewed Research Not a Must-Have for Many K-12 Officials

If some one wishes to be updated with most recent technologies then he must be visit this web site and be up

to date daily.

Very good post! We are linking to this particularly

great content on our website. Keep up the good writing.

Valuable info. Fortunate me I discovered your website accidentally,

and I’m stunned why this accident didn’t came about earlier!

I bookmarked it.

cbd gummies louisville ky just cbd gummies 250mg Can hemp oil cause

heart palpitations