Virtual Reality: Poised to Bring Big Changes to Education?

Predictions Abound, But Evidence Is Still Scant

Virtual reality has been hyped as the “next big thing” for more than two decades, but is 2016 the year that it finally makes a break into schools in a big way?

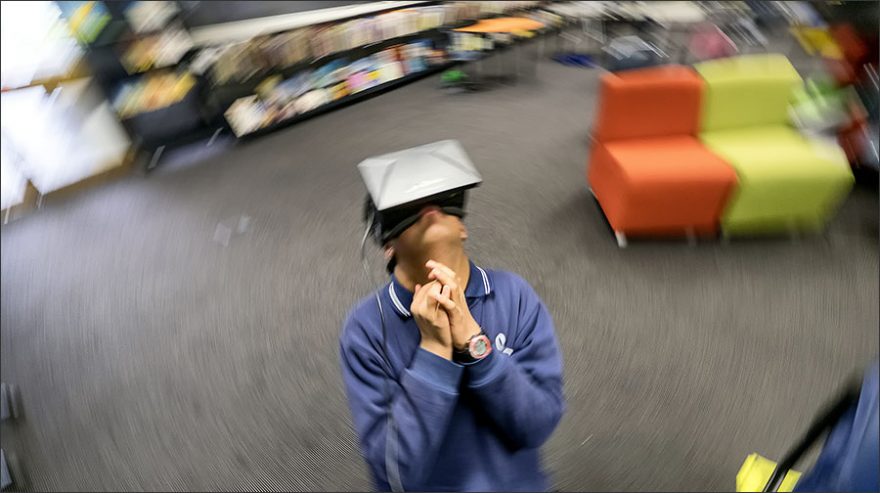

Some might argue it already has. The increasingly popular Google Expeditions—virtual field trips that students can “take” via smartphones tucked into Google Cardboard viewers made out of the material by the same name—are a simple form of VR. Students hold the viewers—which are designed so that their field of vision is completely focused—up to their eyes, use an app that displays the video to produce an immersive experience that takes students to any of up to 150 destinations, and get the feeling of being inside, or at, the location that is unfolding before their eyes.

Still in “closed beta,” Google Expeditions are being tested in schools that pre-register with the company. Schools must apply and be accepted to officially participate in Google Expeditions. Yet it’s not rare to find a school where students have been on these virtual trips.

“More than half a million students have experienced it,” Jonathan Rochelle, director of product management at Google for Education, told an audience of about 500 at BETT, the British Educational Training and Technology show that I attended in London last month, as he unveiled “expeditions” to Buckingham Palace, and the Great Barrier Reef, narrated by David Attenborough.

VR is also one of the trends that venture capitalists are interested in this year, according to an EdWeek Market Brief article by my colleague Michelle Davis.

And more than one-third of tech-oriented people surveyed at a Consumer Electronics Show, or CES, booth in early January identified education as the area most likely to benefit from VR.

“One of the biggest trends we see is virtual reality,” said Mike Fisher, associate director for Futuresource Consulting, a U.K.-based research firm at a presentation hosted by his company in conjunction with BETT. After the show though his company released a report saying that “there was very little practical demonstration” at BETT of the “Internet of Things” in education, other than Google Expeditions via Cardboard.

The View From the Lab

At CES in Las Vegas last month, “education” was identified in a survey as the industry most likely to benefit from the widespread adoption of virtual or augmented reality—the latter a technology that overlays information and images as one goes about day-to-day life, without using an immersive headset. Augmented reality, or AR, is the idea behind the Google Glass headset, which the company suspended production on last year. (As Forbes magazine wrote, “When Google announced that they had invented a device that put a computer in front of your eye, the world collectively gasped. Google Glass was, and is, a stunning technological accomplishment.” The magazine attributed the fact that it was sent “back to the lab” as a failure in launch marketing.)

In that CES survey taken by 1,567 people who stopped at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers booth, 36 percent of participants indicated that the education sector would see the biggest impact and that AR or VR would translate well into areas such as “virtual classrooms and AR/VR-enabled textbooks,” according to a statement by the organization, whose mission is to advance technology.

“Mostly early adopters attend CES,” said Todd Richmond, director of advanced prototype development at the Institute for Creative Technologies at the University of Southern California and a member of IEEE, in a phone interview. “What’s interesting is that, even among people at CES, not everybody had experienced VR first-hand,” he said. “For some of those people, that was the first time they had experienced VR.”

This select audience’s view that education is the most likely realm to benefit from the technology isn’t far afield, said Richmond.

The Institute for Creative Technologies at USC, for instance, has a patent-pending design for a viewer that clips onto a tablet and creates the same effect as a Google Cardboard, he said. “The top part is an immersive 3D (experience), and the bottom half of the display can show text, videos, or be a virtual joystick controller so you can control what you’re viewing,” Richmond explained.

Asked whether VR and AR aren’t likely to be adopted only in schools that can afford it, Richmond said that in 15 or 20 years, these technologies will be “like tables and chairs”—infrastructure that is part of the classroom. “Look at computers,” he said. “They had a small place in the classroom. Now they’re in every classroom.”

In the meantime, he foresees schools setting up virtual reality labs, with a few devices, much like schools once relied upon computer labs, within the next few years.

“The content is a harder piece,” Richmond said. “That’s where the biggest cost is going to be, and where the biggest contribution from outside providers is going to be.” Students and teachers will generate their own user-generated content, too, which will be uploaded to a large-scale repository like YouTube, he said.

And then, there are the age-old K-12 questions to be solved by educators: “While this [VR and AR] gives increased experiential advantage to students…how does it fit into the curriculum? What do you do with that content? And how does that fit with our lesson plans?” he asked.

See also:

- K-12 Venture Capital in 2016: Data Analytics, Virtual Reality Could Make Gains (paid content)

- Google Cardboard Aims to Bring Virtual Reality to Schools Through Simple Means

- Virtual Reality Sharks in the Classroom

- Oculus Rift Fueling New Vision for Virtual Reality in K-12

- ISTE 2015 Kicks Off With Array of Learning, Networking Activities

- Teachers Eye Possibilities With Google Glass

Follow @EdWeekMMolnar and @EdMarketBrief for the latest news on industry and innovation in education.

One thought on “Virtual Reality: Poised to Bring Big Changes to Education?”