Why the Florida Curriculum Adoption Battle Matters to Education Companies

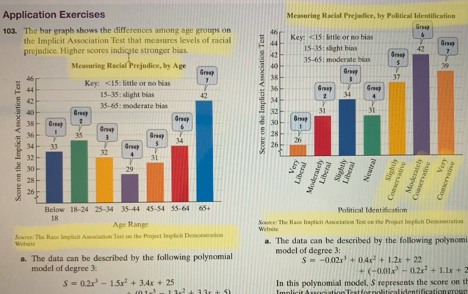

After days of delay, Florida state officials have released a few examples of what they found objectionable in math resources that failed to earn a spot on the state adoption list.

The snippets of text and images — you can see them here — don’t add a whole lot of specifics in explaining the scope of 54 total curricular materials that were rejected because of the state’s belief they include references to the Common Core State Standards, critical race theory, and social-emotional learning.

The state department of education said the illustrations they released were provided “by the public,” and that the agency is still in the process of allowing companies to “remediate all deficiencies” in prohibited materials.

Florida Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran’s office labeled the rejected content as an attempt to “indoctrinate” students. Gov. Ron DeSantis, who appointed the outgoing commissioner, and fellow Republicans in the state legislature have over the past year engaged in a continuous series of cultural battles focused on schools and what they can teach.

But in weighing the importance of Florida’s action, it’s critical to take a step back and look at why the adoption process in that state matters at all.

If an academic resource is turned down for state adoption in Florida, that doesn’t mean districts there are flatly banned from buying it. But getting on the approved list carries a power for curriculum providers that has as much to do with the realities of how K-12 systems make purchasing decisions as it does with the letter of state law.

Here’s what curriculum providers, district officials, and consultants have said about the role of adoption in the market today, and the factors in play that many people tend to overlook.

State Adoption Means Visibility

First, some context.

State adoption processes in big states — most notably Florida, California, and Texas — have traditionally mattered because those states represent such a large share of the K-12 market, overall. Particularly when schools were almost exclusively dependent on print, it made sense financially for publishers to produce a limited number of versions of their resources. So they tended to pay the most attention to the rules of the biggest state markets and customize their materials to meet those states’ demands.

Additionally, those big states have enormous numbers of schools and student enrollments. To secure some measure of approval in a state that serves so many students — Florida has a public school enrollment of about 2.8 million — opens all sorts of doors for curriculum providers, in terms of access and overall visibility.

But over time, things have changed. Digital curricula became much more common, which makes it easier for academic resource providers to tailor materials, market-by-market, and for smaller companies to get in the game.

A Power Shift to Districts

California, Florida, and Texas have all approved policies over the last decade or so that generally give local districts much more freedom to stray from state-adoption lists in making buying decisions. In some cases, those policies were approved in part as a push for local control over curriculum.

Education Week’s Stephen Sawchuk recently wrote a useful explainer on how this local control emphasis gives Florida school districts more power than they used to have. Florida law says that districts must use half of the state funds allocated to them for curriculum purchases for state-adopted materials. They can go off-list for the other half.

Similarly, in California, a state law approved in 2012 gave local education agencies the power to buy materials that are not approved for state adoption, if those resources are aligned to state standards and as long as classroom teachers are involved in the selection process. Texas in 2011 approved a policy that grants local districts the right to stray from the state-adopted list of instructional materials, within certain parameters.

But even with those shifts to local control over curriculum, there’s another important reason that state adoption matters.

Searching for a Stamp of Quality

Many school districts aren’t in the habit of conducting their own, independent, exhaustive reviews of all of the types of curricular resources marketed to them by companies.

They also may not have the time, resources, or expertise to launch detailed studies of whether curriculum materials offered in math, English-language arts, and other subjects are aligned to standards. (See this related story from EdWeek Market Brief.)

So districts end up relying on whatever outside sources of information or expertise they can get. In some cases, that includes word-of-mouth recommendations of superintendents or curriculum directors in school districts they know.

Absent other sources of information, getting on a state adoption list is seen by some K-12 officials — rightly or wrongly — as an imprimatur of quality, a sign that an outside entity has reviewed a company’s academic resources in detail, looked at their alignment to academic standards, and found them worthy of being used in classrooms.

The Takeaway: It’s unclear how, exactly, school districts in Florida will react to the state’s new list of sanctioned materials.

But barring anything unexpected, it seems likely the state’s approved list will at least have a strong influence on district-by-district buying decisions — even if the state’s up-or-down vote is not as strong an influence as it once was.

And it also seems certain that curriculum providers thinking of submitting materials for adoption in Florida are weighing a set of issues that they never considered before.

Photos: Images of two unidentified math resources that Florida state officials said last week did not meet their standards.

Follow EdWeek Market Brief on Twitter @EdMarketBrief or connect with us on LinkedIn.

See also:

- States Are Restricting Lessons on Race, and It’s Poised to Shape the K-12 Market

- How State Curriculum Adoption Cycles Are Being Thrown Off by the Coronavirus

- Florida Officials Reject Long List of Math Curriculum Materials, Citing References to Critical Race Theory, SEL

- Special Report: What Social-Emotional Learning Products and Programs Do Districts Want?