Thousands of American students were able to return to class in person during the last weeks of spring, after a year of remote or hybrid learning. When the kids showed up, educators could see even more clearly how uneven their learning has been during the pandemic.

Last year, researchers at NWEA, an independent nonprofit assessment company, published an analysis of data from the autumn 2020 MAP Growth tests of more than 4 million public school students. They found that students’ reading scores were mainly on track compared to the previous year, but their math scores were five to 10 percentage points lower on average.

“Frankly, students didn’t lose anything, they just never had the opportunity to learn it,” said Allison Socol, an assistant director at The Education Trust, a nonprofit education research and advocacy organization. “When given the opportunity, then they will succeed. And so we always talk about it as ‘unfinished learning.’ ”

Now, as schools launch summer programs and plan for the fall, they’re left with a tremendous responsibility (and a windfall of federal money) to try to fill in the gaps for students who have spent a year trying to learn through a computer screen.

Related: The simple intervention that could lift kids out of ‘Covid slide’

Researchers and educators are considering various methods to fill these gaps, including small-group instruction, extended school hours and summer programs. But, while the results of research on what might work to catch kids up is not always clear-cut, many education experts point to tutoring as a tried-and-true method.

One-to-one and small group tutoring are “by far the most effective things we have that are practical to use in schools that scale,” said Robert Slavin, an education researcher and director at the Johns Hopkins Center for Research and Reform in Education, in an interview before his death this spring. “We compared tutoring to summer school, after school, extended day, technology and other things. And it’s [a] night and day difference.”

Guilford County Schools turned to tutors early in the pandemic to confront unfinished learning. The district, with 126 schools (including two virtual academies) and nearly 70,000 K-12 students, created an ambitious districtwide tutoring program using a combination of graduate, undergraduate and high school students to serve as math tutors. Now, over the next few months, the district hopes to expand their program to include English language arts and other subject areas and plans to continue it for at least the next several years.

“What we know is that learning loss is going to look different from student to student,” said Dr. Whitney Oakley, the chief academic officer for the district. “And that it’s not something we’re going to make up in a summer or in a year. It’s a long road of recovery.”

Devanhi, 12, recently finished sixth grade at Jackson Middle School in the Guilford County district. She lives in Greensboro, North Carolina, with her two parents and two younger siblings.

She learned remotely either full time or part time for more than a year. Although math is one of her favorite subjects, she found some parts of her coursework challenging when she was learning online. For example, she had trouble finding the area of a triangle and other math involving shapes.

Devanhi got an email this spring asking if she wanted to sign up for tutoring, and she quickly replied.

“I’d just get frustrated because I’m just like, OK, I don’t get this problem,” Devanhi said. “But then with my tutor, Natalia, she would help me with breaking it down and helping me, actually being there.”

Devanhi said that her math teacher, Ms. Lineberry, often asked how her tutoring was going.

“She saw how much I improved in math with the shapes and stuff,” said Devanhi. “She would ask a question, and I would be the first one to raise my hand.”

Research suggests that intensive tutoring is one of the most effective ways for kids to catch up on learning. A Harvard study from 2016 sorted through almost 200 well-designed experiments in improving education, and found that frequent one-to-one tutoring with research-proven instruction was especially effective in increasing the learning rates of low-performing students. But less frequent tutoring, such as having sessions once a week, was not. A 2020 review of nearly 100 tutoring programs found that intensive tutoring was particularly helpful in reading during the early elementary years, and most effective in math for slightly older children. And another study found that intensive tutoring had major positive impacts on math gains among high school students.

“Research is emerging that says, if you can provide a high-quality but achievable level of support … you can start to get them accelerating learning,” said David Rosenberg, a partner at Education Resource Strategies, an education nonprofit that assists school districts. “So systems are really trying to figure out, ‘How do we do that?’ ”

“The biggest bang for your buck is tutoring. It’s a little hard to map out an exact perfect scenario, but ensure that those kids have a tutor, ideally, a certified and experienced teacher, and if not, someone who’s getting a lot of training and support, and that those tutors are meeting with those kids from day one of the school year, if not before, to help them catch up,” said Socol.

Rosenberg and others are quick to point out, however, that the other conditions that must go along with that kind of tutoring, like a good curriculum, tailored instruction and teacher support, are crucial.

Related: Takeaways from research on tutoring to address coronavirus learning loss

Guilford County Schools started recruiting their first tutors from local colleges and universities in September 2020 and got them started with the students by November. They focused on recruiting engineering, math and education majors from local schools, including historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

“A&T State University graduates more Black engineers than any other HBCU in the world,” said Oakley. “We are about 70 percent Black and brown in our district, and so it’s very powerful to have tutors serving students who look like them.”

The district decided to focus on math because “research has shown that middle school and high school math ... that’s where the greatest learning loss has been,” said Dr. Faith Freeman, the director of STEM at Guilford County Schools, and the head of their tutoring initiative. “Kids were falling behind in math before the pandemic. It’s just gotten worse.”

The first group of tutors was placed in Title I middle schools, in which low-income families make up at least 40 percent of enrollment. The district prioritized students who were English language learners, students with disabilities, students with a history of chronic absenteeism and students who were struggling in coursework before the pandemic.

On average, Guilford students in the tutoring program received two hours of tutoring each week.

In January, the district expanded the tutoring program by hiring high-achieving high school students to work with the middle school students. Guilford administrators did not disclose their total budget for the program, but it is funded through federal ESSER legislation passed earlier this year to address the impact of Covid-19 in schools. When the district started their program in 2020, they were able to use Title I funding because they focused on Title I schools. Over the course of the 2020-21 school year, 15 graduate students worked up to 20 hours a week, with some earning $14.70 per hour and others nearly $20,000 per semester. The district also had 35 undergraduates, paid $14.70 an hour, and about 140 high school students, paid $10 an hour.

In February, students at Eastern Guilford Middle School took a test, created by NWEA and used by schools across the country, to see where their learning gaps were.

“They took it again in April,” said Principal McNeill. “That showed teachers exactly where students need the most help, because it was able to pinpoint down to skill and standard. So teachers were able to diagnose what was going on with that student in order to prescribe what is needed to make this student more successful and to address those learning gaps.”

After the tutoring, 12-year-old Devanhi said, “I don’t really second-guess myself a lot like I did before. And that’s something that I’ve noticed about myself, because I remember I used to second-guess myself a lot with math or with other subjects. I got more confident with my answers.”

Although there have been early positive signs from Guilford’s tutoring program, historically, not all tutoring efforts have been successful. After the No Child Left Behind law was first passed in 2001, schools got extra money to tutor struggling students, but several frauds and fiascos led to concerns about lax oversight. There were disappointments in other years, too. A 2018 report about a randomized control trial of math tutoring for fourth through eighth grade students in Minnesota found no significant effect on state test scores.

Alexis Obimma, 17, recently finished her junior year at Dudley High School in Guilford County. She took an AP statistics class and also worked about 12 to 15 hours a week at the restaurant chain Papa John’s. She plans to one day go to medical school.

Obimma said that she returned to school in person this spring, but found that she preferred learning online, so finished up the school year online.

Her mom got an email from her high school last December asking if any students were interested in becoming math tutors. When Obimma found out that her ninth grade math teacher was running the program, she applied and was accepted to work as a tutor. She had three students: two sixth graders and a seventh grader.

“I love math. I always was good at math. So it’s easy for me to show them how to do it, show them my way,” said Obimma. “And they usually understand it more easily.”

She spent about two hours a week with each student one-on-one, over the course of two different tutoring sessions, usually during evenings or weekends. One student is studying surface area and three-digit multiplication. Another is studying inequalities.

“What I found easy about it is, when you get to know them, it’s really easier to communicate with the student,” Obimma said. “You’re able to have one-on-one sessions, able to talk about what you like about math, what you don’t like about math, so you can make it interesting for them.”

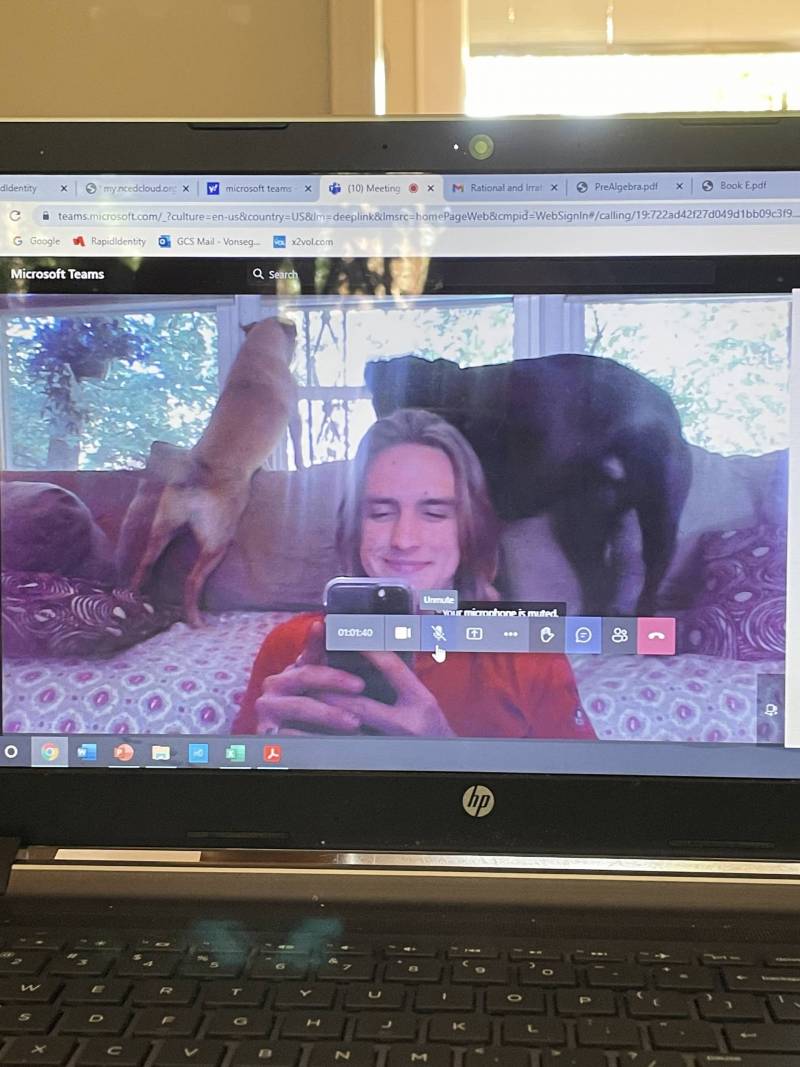

Koen VonSeggen, 17, just finished his junior year at Page High School. He was in honors precalculus and tutored math through Guilford’s tutoring program. His previous jobs included lifeguarding and working yard service during the summers.

VonSeggen said he did well in his own remote learning studies and described himself as someone who’s “never really struggled with procrastination.” Though he didn’t describe his junior year as easy, he said he got all A’s in his fourth quarter, and added that AP psychology kept him interested.

He started tutoring four students in April: two seventh grade girls and two eighth grade boys.

Like other tutors, he debriefed with his students’ teacher at the beginning and end of each week.

“It’s usually like, ‘They did good, everything is all well.’ Or, if a student has a problem, such as, like, isn’t understanding the material as well, I can like, talk to [the students’ teacher] Ms. Magee and say, ‘Hey, you know, so and so might have had a problem with this math problem. So if you see them struggling in your class, maybe they might need to go a little bit slower.’

“It doesn’t usually come to that,” he added.

Related: Research evidence increases for intensive tutoring

Both Obimma and VonSeggen tutored remotely, but some tutors have come back into the classroom along with the students. Dawn Lineberry, the sixth grade math teacher, has a tutor who does both remote and in-person tutoring four days a week.

“I couldn’t have asked for a better person. The kids see her as a teacher,” said Lineberry. “They don’t see her as, you know, as an assistant, they don’t see her as just a tutor. It’s somebody that they know they can trust and get their education from.”

Guilford educators think of the tutoring program as a long-term endeavor for a pandemic that created long-term learning impacts. Administrators hope to triple their current number of trained tutors to serve more students and plan to hire 500 more tutors within the next year with federal funding that will last through 2024.

Some administrators have noticed a difference already.

Freeman said that some math teachers have told her that the performance of students who are in tutoring has increased significantly. Principal McNeill said that a teacher told her that students who had been working with tutors for several weeks scored higher on their NWEA math assessments.

“You know, we haven’t been doing this for that long, right? So I think that we’ll really see even greater growth, not just I think toward the end of the school year, but also the summer and going into this fall,” said Freeman.

One tutor, Kingsley Esezobor, 38, is a graduate student in computational data science and engineering at North Carolina A&T State University. He’s been working with “about 15” students. He says three just need to be reminded about what they already know, three are really struggling, and the rest fall somewhere in the middle — they understand a concept after about two sessions, after which they can solve those questions by themselves.

“Out of the 15 students that I have, I can say confidently that I saw improvements in about 10 students after working with them week on week,” he said.