Sprint Rolls Out Effort to Boost Student Connectivity, Tech Access

Sprint has begun the nationwide roll-out of a program aimed at providing economically disadvantaged high school students with internet access and cell phones. The initiative is one of many large-scale efforts led by corporations in recent years to improve connectivity and access to technology.

The “1 Million Project,” overseen by Sprint and its philanthropic foundation, aims to connect a million high school students from low-income backgrounds across the United States who do not have internet access at home by 2021.

Sprint launched year one of the program in August, and over 1,300 schools across 30 states will have joined by the end of this school year, the company says.

Sprint previously supported a public and private sector project launched under the Obama administration called ConnectED, which arranged to have major tech companies support improved connectivity for schools and students through financial contributions and donations of products and services.

The success of the 1 Million Project, like other corporate-backed efforts to improve student connectivity, will likely hinge on a variety of factors, one advocate who advises K-12 systems said. Those include how easily students are able to connect with districts’ tech platforms and the training that teachers receive.

As part of ConnectED, Sprint made a commitment to provide 50,000 low-income U.S. students with broadband connectivity for four years.

When Sprint was immersed in the ConnectED program, the organization also became interested in moving to close the “homework gap,” said Doug Michelman, president of the 1 Million Project and chairman of the Sprint Foundation, in an interview.

Meaning of the ‘Homework Gap’

The “homework gap” refers to students lacking connectivity away from school, which hinders their ability to do online assignments in the same way their peers who have internet access can.

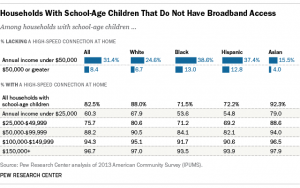

Some 5 million American households with school-age children do not have high-speed internet access at home, and students from poor backgrounds make up a large share of those who lack that connectivity, according to a Pew Research Center analysis, “The Numbers Behind the Broadband ‘Homework Gap.’”

This Pew analysis showed that 31 percent of U.S. households with incomes below $50,000 and children ages 6-17 do not have high-speed internet connection at home. By comparison, only 8 percent of households with children attending school and annual incomes over $50,000 lack a broadband connection.

The results indicate that low-income American households constitute nearly 40 percent of all families with school-age children in the country.

A number of policymakers and private sector companies have urged new efforts to help students lacking connectivity. These initiatives have included providing students with mobile devices capable of getting them online.

While the Obama administration’s ConnectED effort drew praise from some groups, other entities questioned the long-term impact it would have on schools. Some groups cast doubt on whether the program would be sustainable over time and expressed skepticism about the coordination among public and private sector interests. Still, others saw the program as a means for participating companies to build their brands among students and their families.

Given the popularity and ubiquity of cell phones among students, some K-12 systems and educators have sought to use the devices as tools to deliver and have students complete academic content.

At the same time, some educators and advocacy organizations have questioned the extent to which smartphones are able to offer meaningful lessons and voiced worries about distractions these devices may create for students.

Coordination a Must

The success of the 1 Million Project, like other corporate-backed efforts to improve student connectivity, will be determined by a variety of factors, Leslie Wilson, the founder and CEO of the One-to-One Institute, said. According to Wilson, Sprint’s program should be judged by more than just its ability to provide students with basic connectivity. The real benefits would only occur if increased connectivity helps students connect with their district’s tech systems and increases academic opportunities, she said.

“The tendency will be to emphasize how great it will be to have children connected to the internet at school and at home,” Wilson said. “But the challenge is how to integrate a device into a school’s network.

“To just get the devices, put them in the hands of kids, and hope that something good is going to happen will be disastrous. It is imperative for a systemic approach to be in place to implement and maintain the program.”

Wilson’s nonprofit organization consults with schools and districts on how to implement technology programs. She served as co-director of Michigan’s statewide one-to-one initiative from 2002 to 2003.

Wilson said her organization was in contact with Sprint and advised the company on the program’s development. She said that supporting teachers and administrators in implementing the program will be critical to its development.

“The professional learning that goes with the program on the side of teachers and administrators is crucial to its success,” Wilson said.

Wilson also cautioned that the program could carry “hidden costs” for districts in keeping up the effort and making sure the technology is coupled with meaningful lessons in the classroom. She noted that the 1 Million program’s website says there must be a school or district leader for the program, or another individual overseeing its operation.

Sprint Corporate Communications Director Lisa Dimino noted that Sprint’s program could be integrated seamlessly into school systems, without placing additional financial or tech burdens on districts. The program can help students access online platforms outside of school, she said.

“We work closely with each school district to determine the best use of the technology for their students and to directly manage getting the hundreds of thousands of devices to the participating students,” Dimino said. “That’s the reason that we require an administrator or leader from each group.”

The program “is completely free for those schools and the students,” she added. The 1 Million Project provides students access to free Wi Fi and the ability to continue their studies outside of the school’s grounds, Dimino said. “There is no real integration into a school system other than students being able to access their Google Classroom, or another service being used by a school.”

Growth of Program

Last December, the 1 Million Project launched a pilot program for 4,000 students in 11 cities, including Chicago; Kansas City, Mo.; and San Diego. Sprint later announced a fundraising website ahead of the program’s national start to raise donations from its customers and other individuals who wanted to support the program.

In addition, the company encouraged schools and districts to apply online to benefit from the program’s free devices and data. The 1 Million Project received more than 275 applications from schools and school districts hoping to participate, Dimino said.

One such place was Communication and Media Arts High School on Detroit’s west side, where Sprint provided all 179 of the school’s 9th graders with a free smartphone and 3 gigabytes of data access. According to a Detroit Free Press article, 2,000 ninth-graders in the Detroit Public Schools Community District, which Communication and Media Arts is part of, received free Samsung devices and data for five years starting on September 22.

Donya Odom, who recently began her seventh year as principal at the school, said the program has been essential in closing the technology gap and promoting the academic success of students.

“Being able to access the internet on a smartphone enables a student to stay competitive academically, have access to their teachers via e-mail, and use various academic platforms that teachers rely on to give students correction and guidance,” Odom explained.

Dimino elaborated on why the program is expanding opportunities for participating students. She said prior to the program, many high-schoolers stayed after school, went to their local library or a fast-food restaurant, and even waited until a relative returned from work to access an internet connection.

“When we talk about this program being a game-changer, we mean that those students can focus on the schoolwork, and not how to get the schoolwork done,” Dimino said.

As the program has taken hold, Odom said she has noticed a change in participating students’ academic engagement and self-reliance.

Teachers in Algebra 1 and Biology classes said they have seen a 30 percent increase in students using the online platform to complete assignments—an increase that educators attribute to the use of smartphones.

“They are taking more ownership of their academic success,” she said, “and they are being more responsible. Students are very much protective of their smartphones. We told them that the phones are just another type of textbook, and they need to look at them as a vehicle by which they can be successful in class.”

Sprint lists the requirements for high schools and districts to participate in the program on the 1 Million Project website, along with contact information to ask questions about applying. The 1 Million Project is accepting applications to be part of Year 2, which will begin with the 2018-2019 school year.

This post has been updated with additional comments from Sprint.

See also:

great story

I am founder of a new community based organization. This Sprint Tech Implementaion sou ds Great. Would, can a CBO be a part of this in an after school setting???

Hi Robert, I am not certain if a CBO can get involved with the program. I know that the 1 Million Project is tailored to the needs of schools and districts, so your after-school program may qualify to benefit. Here are links to the program’s official site for interested schools and the online application: http://www.1millionproject.org/schools https://sprint.custhelp.com/app/forms/1MGrantForm I hope these links help! Let me know if you have any further questions about the story. Thank you, Leo

Hello, I am a 5th grade Math/Science teacher working in the South Bronx, New York area. Over 90% of our students receive free lunch due to the low-income of our student’s parents. We have an overwhelming amount of students who do not have computers nor internet at home. Our local school has purchased the computer iReady program that has cost thousands of dollars from our school budget to improve the ELA & Math scores of our kids but our students can not utilize the program at home. In my classroom I also provide homework assistance through several websites but these students can not benefit from them. I am aware that you provide for high school students computers/internet. Have you ever considered 5th graders in elementary schools. We are preparing these students for Middle School but the economic disadvantages they have make it almost impossible to place them in the same level as other students with better financial support. I would like to know if you would consider to begin a pilot program for 5th graders and would you consider our school (P.S. 150 – Bronx, NY). It would be such an enormous impact for our staff and for all our 5th graders. Please consider this idea.